Monday, February 2, 1987.

I was a 19-year-old sophomore at Cal.

It was a rainy morning in the Bay Area, and my Converse were soaked by the time I made it to my German Literature class on the third floor of Berkeley’s Dwinelle Hall.

I had a coffee from the vending machine to warm me, and the class passed quickly – we were reading Lessing’s “Emilia Galotti,” a work with which I was starting to fall in love. (Lessing almost had me change my major to German.) At noon, the professor – I can see his face, but not remember his name – dismissed us.

I was hungry, and wanted to head back to my home – a co-op on Ridge Road – for lunch. The rain was still falling, and the staircase in Dwinelle was crowded and wet. The skid tape on the steps was worn down, my tennis shoes were old and treadless, and everything was damp.

The predictable happened. My feet went out from under me, and I landed hard on my bottom, my head snapping back and striking a metal railing. Several people helped me up, and I laughed it off. I was embarrassed at my own clumsiness, and though my butt hurt, my pride was far more wounded.

I made it down another flight and --

I woke up in the back of an ambulance. According to my friend Darragh, who had been behind me trying to catch up after my first tumble, I stopped, stood stock still, and then fell backwards, my body rigid, the back of my head hitting the floor before the rest of me. Years later, Darragh told me she still had nightmares about the sound my skull made when it struck the marble.

People screamed. Apparently, I opened my eyes after a few seconds, but did not respond to any prompts. Someone called 911, and the paramedics bundled me onto a stretcher. I was unconscious for about 20 minutes.

I was taken to Alta Bates hospital, given a CAT scan, and held overnight. I was diagnosed with a bad concussion, told I’d have a monstrous headache for a few days, but should recover completely.

What I remember most was that I spent half that night in the hospital throwing up, and the other half being woken by nursing staff checking to make sure I didn’t slip into a coma. The next day, Mrs Richardson – an old friend of the family – collected me from the hospital and took me to her house in nearby Piedmont. I recuperated on her couch for another 24 hours, but by Wednesday afternoon, was ready to go back to my worried friends at the co-op. By Thursday morning, I still felt a little weak and woozy, but was ready to go back to class; by Sunday, I felt right as rain.

I was not right as rain.

Six weeks later, I was hospitalized on a psych ward for the first time.

This morning, more than 35 years on from that Groundhog Day tumble, I had a two-hour meeting with a psychiatrist on Zoom. Dr. Frederick and I reviewed the results of a series of SPECT brain scans I had last month. It’s only in the last few years that I’d begun to wonder if that 1987 concussion had had an effect on my mental illness; in the 1980s and ‘90s, the focus in therapy was always on adverse childhood experiences and genetic inheritance. It’s just recently – partly thanks to research into the long-term brain damage suffered by football players – that we’ve begun to see how traumatic brain injuries can play a pivotal, even central role in the development of mental illness.

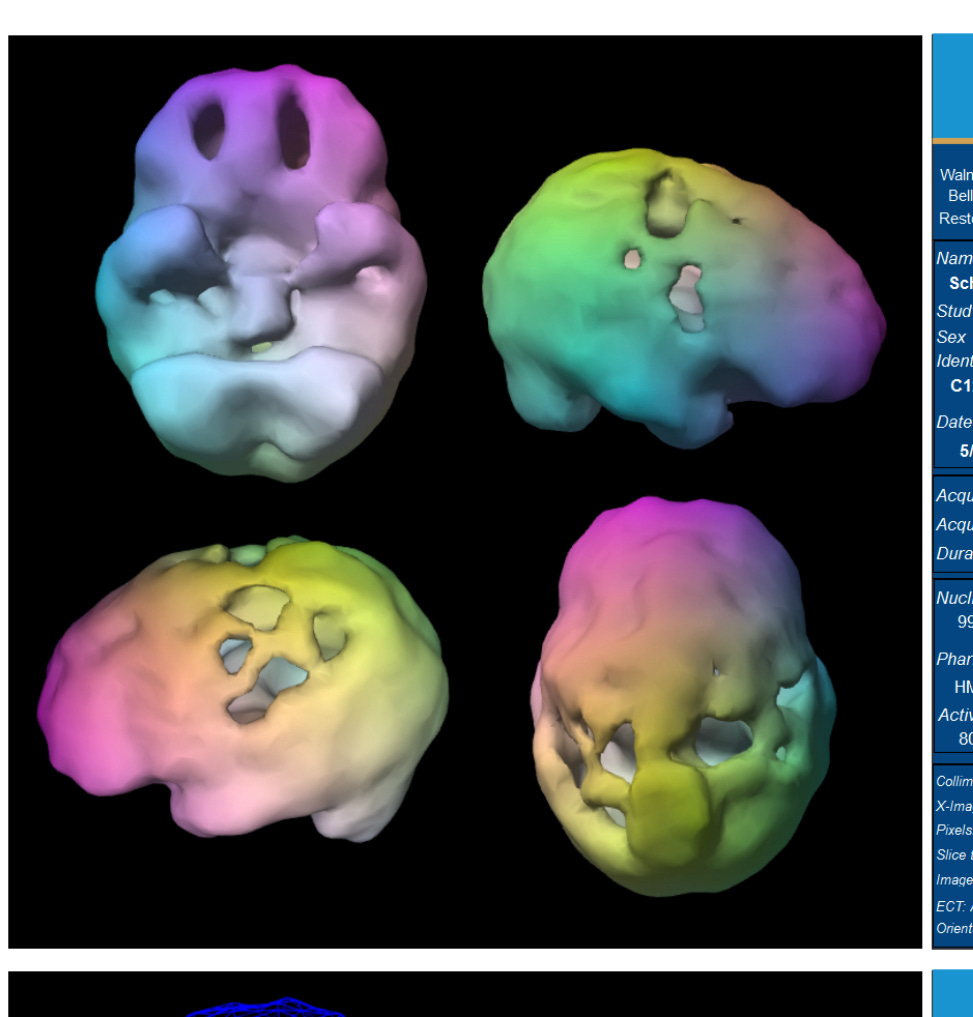

Today, Dr. Frederick showed me images of a dozen scans of my brain. There were pockets and holes where there should be smoothness; there were strange bumps and divots consistent with traumatic brain injury and some evidence of progressive encephalopathy.

“It looks like you were hit several times – or had one very severe concussion,” Dr. Frederick said; “There’s no question that you had a TBI (traumatic brain injury) and to one extent or another, you’ve been trying to cope with the consequences of that since you were 19.”

I started to cry.

I am not yet sure what this all means. My first thought was and is relief: I am not making all this up. This is not just some genetic thing I am destined to pass on to my children. There’s a why. At last, at last, a why.

Here’s a SPECT scan of a “normal and healthy” brain of a middle-aged man.

Here’s mine.

Dr. Frederick brought a compliment: “Given the extent of poor function in multiple areas of your brain, your overall success is commendable. You’ve been dealing with a formidable handicap that you didn’t realize you had.”

And from the doctor’s written notes:

A combination of findings suggests past brain injury. These findings include: -

· Decreased prefrontal pole activity -

· Decreased cerebellar activity -

· Decreased temporal lobe activity

· Decreased parietal lobe activity

· Decreased occipital lobe activity

· Decreased dorsal prefrontal cortex activity –

· Decreased periventricular tracer activity.

· Mild scalloping seen on both studies, more pronounced at rest.

This is an explanation, not an excuse. But it perhaps provides some context for why I have made these monumentally impulsive and reckless choices, why I self-injure, why at the worst possible moments, I feel compelled to choose the least healthy decision. I can romanticize my illness all I like – but what if it mostly comes back to one hell of a bad bang on the head when I was 19 years old?

There are a variety of treatments on tap, treatments I cannot discuss yet – some covered by insurance, some covered by my very generous family. There is some worry that left untreated, I am at higher risk of dementia in the next few decades. Dr. Frederick is reassuring, and says that that danger can be mitigated, and perhaps the worst effects of this brain injury outright reversed.

And here’s the real hope: if so much of my impulsiveness, my despair, my self-destructiveness, my mood lability is the consequence of a physical injury that can be healed, then I do not need to spend every waking moment contemplating my sins and errors and shortcomings. You fell down a flight of stairs, Hugo old bean, and it changed your life, and now that you know, you can start to move forward.

I am in a world of shock at this news, but filled with optimism – and even more likely now to discourage my son from playing tackle football!