I don’t know if you’ve heard, but a submersible has imploded in the ocean. Five people died.

You have heard, of course. To have not heard about the desperate search for the Ocean Gate Titan, missing on its journey into the depths, would be something of a feat. If you are reading this on your laptop or your phone, I find it difficult to imagine that same device hasn’t brought you updates on the sad fate of a little vessel, a bulbous cylinder that disintegrated on its way to visit the most famous shipwreck of modern times.

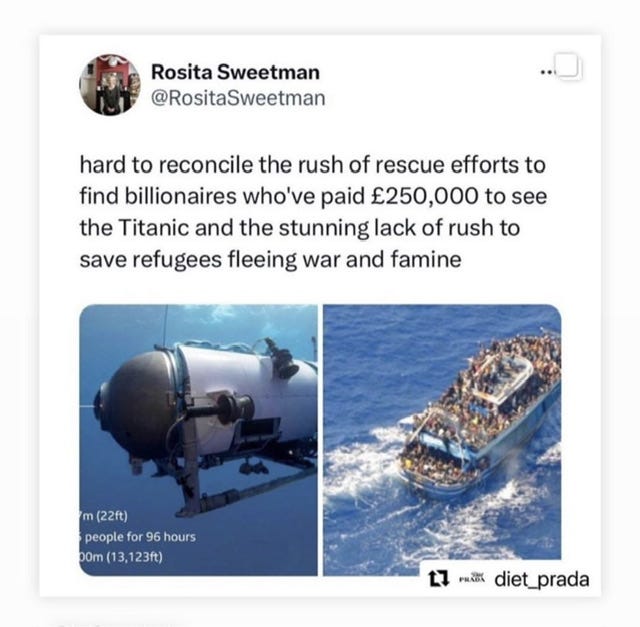

Until the wreckage of the Titan was discovered on the seabed, we had constant coverage with no real news. That meant a proliferation of viral memes, wild speculation, and everyone’s favorite activity – expressing horror at how everyone else is having the wrong reaction. Some noted that a refugee ship had capsized in the Mediterranean the same week, leaving hundreds of migrants missing and presumed dead. Where was the empathy for them?

Some people made tasteless jokes, as people generally do after a tragedy. This has been going on for a long time. Less than 12 hours after the Challenger blew up in January 1986, long before any of us had the Internet, I heard my first shuttle joke from a housemate in my Berkeley co-op:

Q: What did Christa McAuliffe say to her husband this morning?

A: You feed the kids, honey. I’ll feed the fish.

Paul told the joke to the dozen of us in the Ridge House living room, watching the evening news coverage of the disaster. The joke started a heated argument between those who thought it perfectly human to make light of tragedy, and those who thought it was cruel and offensive. I was not quite 19, and it was one of the first instances I can remember of people earnestly trying to police each other’s feelings about a news event.

We are a people obsessed with telling other people how to feel. Half of social media seems devoted to telling other people that they are disgusted by what should not disgust them, and untroubled by what should upset them. Your empathy is misplaced. You are doing feelings wrong. Weep for this, not for that. Be upset at this, not that. Worry about this, not that.

That housemate who made the ghoulish joke about the death of the “teacher in space?” Paul was a music major, and when I told him I loved Handel, he replied, his voice drenched in scorn, that I loved music designed to flatter and soothe the already comfortable. If I wanted to grow as a human being, I needed to listen to Shostakovich and be unsettled. “Music shouldn’t reassure you. It should challenge you.”

I nodded at Paul, made some self-effacing remark about already feeling very challenged by my Latin class, and changed the subject.

In our hyper-partisan age, the politically inclined study the tweets and posts of their opponents, looking for evidence of Wrong Feelings and Empathy Failings. They then repost what they find for their own followers, or repurpose the tweets for fundraising:

Hugo, can you believe what these crazy Democrats said? Look at this tweet! They hate America.

Hugo, can you believe the Republicans won’t do anything to address America’s real problems? Look at this tweet! They hate America.

Part of living in society is learning that not everyone cries or laughs at the same things. Humor and sentimentality are mediated by culture, and by our own individual personalities. Both left and right take a great deal of self-righteous satisfaction in clutching their pearls when someone laughs at What Should Not be Mocked or fails to weep for What Should Always Engender Tears if You are a Good Person. The irony is unmissable: our denunciations of others for failing to feel empathy as we think it should be felt is itself evidence of our own failure of empathy.

I am a poetry person. I look to poems and country songs for assistance in clarifying how I see the world, or to help me see what I haven’t seen before. In one of his most famous (and famously difficult) works, Dylan Thomas declares his refusal to mourn the death of a child he’s never met, but whose tragic end is described in the newspaper. The last line is the one that everyone remembers from English class: “After the first death, there is no other.”

After Uvalde, how do we weep for the submersible? After Auschwitz, how do weep for Columbine? After grandpa has died, how do we weep when we put the dog to sleep? How do we continue to feel some griefs and not others?

I shall not murder

The mankind of her going with a grave truth

Nor blaspheme down the stations of the breath

With any further

Elegy of innocence and youth.

Fair enough, sir. But you go too far, dear drunken Welsh poet, if you imply that our grief over a dead child we never met or five rich imploded mariners is blasphemy, insincere, or inhuman. Your views are yours, Dylan, and they are eloquent (although kinda opaque, if you ask me), but you are entitled to them. Just don’t presume they are guardrails for the rest of us.

It is a mystery that we feel what we feel the way we feel it. A mystery, however, is not a failing. The jokes are not failings. The curiosity is not a failing. The preoccupation is not a failing.

I am a both-sideser in a world contemptuous of both-sidesism, and I am a both-sideser because of temperament, upbringing, and trauma. You are who you are because of your own particular composition of experience, biology, and belief. Weep for what you weep, laugh at what makes you laugh, and as much as is possible, resist the urge to denounce those who weep and laugh differently for failing at the task of what it means to be human.