Some news:

I have signed a contract to produce a book for a private client by the end of the year. It’s going to be a heavy lift, but it’s a very well-paid lift, and I’m grateful for it. As a result, I’m not taking on additional writing work until early 2023, and my “posts” here will be less frequent. I’m extremely grateful to the friend who worked hard to arrange this gig for me, and I’m grateful to everyone who has shared and promoted my ghostwriting and coaching business. Thank you!

Last week, in a Facebook post contemplating the start of the new school year (perhaps our first “normal” year since 2018-19), I mentioned that I was in awe of my children’s comfort with other people. My kids are both popular in their social groups, and they are good with adults. They dote on small ones younger than themselves. Even grumpy cats seem to adore Heloise and David. This high likability score is in keeping with their mother’s childhood and adolescence, but not their father’s. To say I was an awkward loner would be to undersell the degree to which I was uncomfortable in my own skin.

Make no mistake — I am not drunk on paternal pride, just a little tipsy, as that ancient intoxicant pulses through my veins. Heloise and David are not perfect little angels, not models of decorum, not exemplars of charm and civility. They are kids, and they are human, and on not-infrequent occasion, exasperating in that humanness. I am still proud of them, and proud of the way they are instinctively generous with their affections and interests.

I shared about this last week, and a Facebook friend — a new parent — asked:

Curious minds of fellow parents would like to know how you placed emphasis on such concepts as social skills and charm and manners. How did you do it without being overbearing or disregarding the development of their own identities?

Regular readers will know that manners are my second favorite topic, after my compulsive need to revisit the least savory aspects of my own colorful life. I’ve written that manners are the only thing that have sustained me in difficult times, and that they are one of the most important things I am called to pass on my children. What I haven’t done is write about what it is we actually taught — and teach — our children?

Some of this is fairly straightforward: we started in on “please” and “thank you” when they were tiny. When Heloise was an infant, and I would change her diaper, I would describe what I was doing. I would smile at her, and thank her for letting me be her daddy. Even with a six-month-old, I wanted to convey that I knew her body was hers and not mine, and I was grateful for the trust that her soul had placed in mine. She had no agency yet, but I was deliberately deploying the language of individual autonomy.

When she, and later her brother, got older, we began to gently prompt the “please” and the “thank you” — and modeled those phrases for them. We eventually moved on to table manners, and how to walk through a door. When there was pushback, their mother and I would say, “This is part of how we show love for other people, and when you’re older, you might decide it’s silly, but for now, this is what we think is best and it’s what you will learn.”

You can buy etiquette handbooks online, or pay for expensive courses where they will teach you how to walk, how to sit, how to navigate dinner parties and table settings and office parties. There’s a lot of useful information in these books — I still consult various old manuals for tips — but there’s no question they’re written mostly for the upper-middle class and those eager to imitate them. In the end, while it is nice to go to places where there are both fish forks and cake forks on the table, it’s obscenely reductive to claim that all there is to manners is knowing which one goes with the salmon and which with the Sachertorte.

At the heart of what I teach my children are two things: disgust is your enemy; curiosity, your ally.

No human feeling, not even jealousy, builds walls faster than expressions of disgust. Think about the social issues that tear us apart. Think about the words that come to mind when you contemplate the errors of the other side:

Drag queens reading to children: disgusting!

Shoppers refusing to wear a simple face mask in a pandemic, rawdogging the air: disgusting!

I’m disgusted that anyone could vote for Trump.

I’m disgusted that anyone could support tearing a baby apart inside its mother’s womb!

Seeing Black people vote Republican makes me want to throw up!

I’m disgusted that we still have Confederate monuments in 2022!

It’s disgusting to see two men kissing!

People say these things, returning again to expressions of disgust as the most intense form of disapproval. It’s a return to an early developmental stage, where so many foods your parents want you to try end up revolting you. Expressions of disgust are a very early way of asserting autonomy, and establishing how you are different from your parents: Broccoli is disgusting. Cottage cheese makes me puke.

I happen to agree about broccoli’s unpleasantness.

The problem is that as Junior starts to grow, he learns that other things are disgusting. In most families, by the time Little Llama is in first grade, he or she knows that there’s a veritable litany of disgusting things besides food: His parents drive past a homeless encampment, and instead of expressions of empathy, talk about how vile the unhoused are. Mama points out a billboard for a crisis pregnancy center and declares that pro-lifers are disgusting liars, preying on the vulnerable. A secular father drives by an Orthodox family, walking on Shabbat, and declares it disgusting that in this day and age, some people feel it’s okay to have nine children. A conservative mother takes her children to the beach, and declares herself revolted to see so many teen girls strolling around, their buttocks bouncing free in the sea breeze.

Disgust lies at the root of contempt.

I have been very, very explicit about never using expressions of disgust about anything, food included. I certainly make my preferences known, but even when the children were small, couched them in a language of individual choice, not universal truth. Some people like vanilla ice cream, some like mint chip, and some think eating sweet desserts made with cow’s milk is wrong. Some people are homeless and may smell bad; some people are very rich, and drive beautiful cars and live behind high gates. You are permitted to develop political views about wealth and homelessness, darling little alpaca, but you are to be kind to the homeless and not grimace when their odor hits you so hard your knees want to buckle.

There’s a difference between being street smart — aware of your surroundings and possible threats — and declaring those potential threats to be offensive and immoral.

In our family, we make our kids try many many many new things. They have eaten snails and they have chowed down on menudo followed by halo-halo; they have tried fried gator and tasted hormigas culonas. They have danced with the Torah at midnight, and they have been to Easter Sunday mass and to a gospel-driven funeral at the Church of God in Christ, in the heart of Black L.A. They have been guests at events at the Jonathan and Valley Hunt clubs, and gone to cramped-apartment-birthday parties for Guatemalan refugees in the heart of Pico-Union, the poorest neighborhood in this vast city. Two elder members of the Hawthorne Blood Pirus (our local gang) greet my children enthusiastically every Friday night as we walk past the liquor store, and my children wave cheerfully at Ryan and Andre.

Good manners do not require that you go hither and yon, trying everything. (It’s easier for my family because I need to do things with the kids that don’t cost a fortune — and we happen to live in the middle of one of the world’s great cities.) Good manners simply require you not to be innately suspicious of novelty and difference.

The opposite of disgust is not a refusal to make any distinctions at all. As I remind the kids, you get to try tripe or giant fried ants and decide that you’d like it very much if you never tasted them again. Trying everything doesn’t mean loving everything. But three things are essential: you must try it once; you must be polite to the person who offered it; you must remember not to universalize your own negative experience. Your distaste is yours, and others are likely not to share it. As with menudo and deep-fried Mars bars, so with virtually everything else. (The exceptions include of course, illicit drugs, genuinely life-threatening experiences like getting in a car with an obviously drunk driver, and sexual encounters for which one is not prepared and about which one does not feel particularly enthusiastic.)

The opposite of disgust is curiosity. The world is such an interesting place, I tell my children, and I wish I could fly them off to see Macchu Picchu and the Eiffel Tower and the Pyramids, but today we shall instead go to Filipinotown. Tomorrow, we might go to the fashion district, and then, maybe, accept that invitation from one of my co-workers at the store to a not-quite legal cockfight; next week, we’ll be at the Hollywood Bowl in the cheap nosebleeds, hearing Wynton Marsalis, Angelique Kidjo, or Pitbull. When we are at the ranch, we shall wander among the live oaks and the elms, and hear what the ancestors have to tell us. Again, I tell my children, you don’t have to like it all equally — but you must be curious about what moves and excites others.

Nothing makes people feel happier than to know you take a genuine interest in their world. The essence of good manners is to be interested, and the problem is, not everyone is equally interesting to us. So we practice being polite spectators and consumers of as much as humanly possible, so that we are ready and willing to roll with whatever and whomever we encounter in the classroom or on the playground.

Nearly 30 years ago, when I had first talked my way into teaching a college women’s studies course, one of the more senior professors in the discipline confronted me. Why did I, this young white man, want to teach this? I gave a pro forma answer about the way in which women’s lives and experiences are often ignored in traditional narratives. Professor Ling shook her head, and said, “That’s not good enough. We teach women’s studies in order to raise up young feminists.” I pointed out timidly that that seemed to erase the distinction between education and indoctrination, and the professor replied that rightly practiced, all education is about equipping young people to fight the Great Crime. I nodded, and said I would do my best.

I suppose, in a way, I am more like Professor Ling than I thought. I too want to equip my kids to fight the Great Crime, except that I rather think the Crime is nothing more than contempt, disgust, and suspicion of others and their plans. Good manners, which manifest in “please,” and “thank you” and “tell me more about that, that’s so interesting,” are themselves tools to disarm, to heal, to comfort. My Christian friends quote St Paul, who said “Though we live in the world, we do not wage war as the world does.” I say that to my children too, not because I see them as missionaries for Jesus or Torah but because I want them to fight against the overwhelming cultural forces that tell them that half the nation is in thrall to madness and ignorance, or sin and conspiracy; I want them to have the courage to be warm and engaging when it’s difficult as well as when it’s easy. I want them to say to the zealots of the world, “I see your passion, tell me more” without feeling compelled to adopt whatever constrained and cramped world view is on offer. I want Heloise and David to be who they are, but to take that “are-ness,” that self-identity married to purpose, and let it make them curious, warm, empathetic, and non-judgmental.

Francis Bacon (the essayist, not the painter) famously remarked “If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end with doubts, but if he will be content to begin with doubts he shall end in certainties.” By trying new things, and meeting new people, and being as winsome and gentle and curious and open-minded as possible, my children have a chance to find their own real, deep, life-tested certainties.

In the meantime: close your mouth when you chew, shake hands firmly but not too hard, stand up when grandma comes into the room, don’t wear navy with black, try what you’re offered, and remember that every single person you meet has a remarkable story to tell.

__________________k

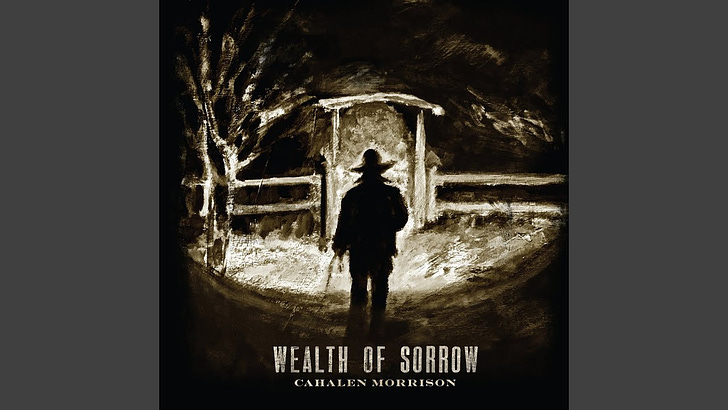

I’ve had the new release from country-folk singer Cahalen Morrison on repeat lately; this is one of the most striking and evocative songs I’ve heard in a long time. Recorded live to tape, it’s simply breathtaking.

What of the silence among the stars?

What of that wealth of sorrow?

I’ll sing a song so sad and true

That the stars will line to light my path,

And point me toward your dear affection.

“Heloise is certainly in that phase of disgust.” Interesting diction and perspective in relation to your post on privacy. Although it’s true: you don’t don that expression visually. Unfortunately the same cannot be said about me. Oh well!