I do not charge for subscriptions any longer, and my writing is free to all, but if you are interested in supporting me and my work, I would very much welcome the one-time or occasional cup of coffee. You can buy me one here, and it will go to the “keep me caffeinated to cope with the avalanche of freelance” fund. Thank you!

My new website for my writing and coaching business can be found here.

“Oh man. I can’t visit you there.”

Sergio feigns sadness. Sergio is one of my managers at Trader Joe’s, and though he is less than half my age, he is a competent and experienced leader. He was, until recently, my neighbor as well. My wife and I moved last week — a short move of less than two miles, from Hawthorne to Lawndale.

(If you’re not from Los Angeles, and perhaps even if you are, those names mean little. To summarize, each is a small city in the southwestern part of our vast county. Hawthorne is slightly famous as the home of The Beach Boys and SpaceX; Lawndale is, as best I can tell so far, entirely undistinguished save for its slightly absurd, Chamber-of-Commerce-manufactured name.)

Sergio grew up in a gang. He has left that gang behind, but old allegiances and reputations do not die easily. The street to which Victoria and I have moved is another gang’s territory; even in his Trader Joe’s Hawaiian shirt, Sergio might be picked out as a most unwelcome interloper should he stroll down our section of Prairie Avenue. He’s not really sad, as he never visited me at my old home anyway; his affectionate teasing, however, binds together congratulations on our move with a sober acknowledgement that for many like him, a single block can mark the border between home and hostile territory. What a middle-aged white man can traverse with ease, a young Hispanic fellow, a onetime Hawthorne Piru, goes only at his peril. Perhaps it would be fine if I invited Sergio over to watch a game in our apartment. Almost certainly it would be fine. Sergio is young, but he already has three little children. In his world, “almost certainly” is not assurance enough.

For me, to move from Hawthorne to Lawndale is to move from one barely understood community to another. Yes, I have read a little of the history of these bedroom towns that exploded in size after World War Two; I certainly know that the Beach Boys met at Hawthorne High, and that Lawndale was once almost entirely populated by employees of Northrop Grumman and McDonnel Douglas. Surf music, beach volleyball, hardcore punk and aerospace built the South Bay of Los Angeles generations ago. I know these facts because I’ve read them, but I don’t know that when I cross Prairie Avenue, I slip from one contested territory to another. The real visceral importance of place here is lost on me. I may live in Lawndale the rest of my life, but I will never be of Lawndale. It is an address, not a mold.

I was born in Santa Barbara and raised in Carmel by-the-Sea; I spent summers and holidays on the ranch my great-great-grandparents built, nestled on the slopes of Mission Peak in the East Bay Hills. If you ask me where I am from, I will tell you one of those three places. I will be careful how I tell you of them. Santa Barbara and Carmel are two of America’s most idyllic and mythologized beach communities. Because they are both famous and tourist-trod, many people who have visited for a day or a weekend tell me I must have been terribly lucky to be born and raised in such lovely, desirable places. I know better than to tell them otherwise.

A famous view in my hometown.

(Two friends recently had a wonderful discussion about place and politics: check out this conversation between my friends Pete Turner and Joshua Treviño.)

Rich white kids who grow up in comfort do like to write damning, deadpan exposés of their glamorous hometowns. Bret Easton Ellis was 21 when he wrote Less than Zero, a devastating (if now, very dated) takedown of West Los Angeles hedonism. I read the book before I moved to L.A., and for years after I moved here, it shaped much of my wariness about the angel town. (So too did country music, which has an entire canon of songs that mock Los Angeles. There is no city, not even Gotham, that evokes the same contempt from Nashville as does L.A.)

Being from Carmel and Santa Barbara, and living in L.A. with vacations on a ranch, I felt that even at my poorest and most desperate, my roots were sunk deep into the soil of privilege. That soil was fertile ground for the already prosperous to become more so. It was also strangely devoid of magic. I grew up wishing I were from Oildale like Merle Haggard, or some slipping-down town on the Jersey shore like Bruce Springsteen. When you already live in the place of which others dream, you feel as if your luck has robbed you of romantic aspiration. The hero’s journey starts in desolation, or at least in the mundane. When you can walk out your front door to see a coastline immortalized by Ansel Adams and Robinson Jeffers, and when you are a boy where others dream of retiring, all that quotidian loveliness somehow retards your vision of what’s possible. Auden, in his take on the Georgics, shuddered at the thought of living on the tedium of the plains: “Think of growing where all elsewheres are equal!”

I grew up in paradise, and I relate.

Strangely enough, when everyone tells you you live in Shangri-La, all elsewheres are equal. In my adolescent rebellion, I wanted to live in a place that wasn’t desirable, a forgotten place, a disparaged place, a place whose utter unremarkableness would allow me to be, if not remarkable, at least not overshadowed by the grandeur of my home.

The Eagles, the quintessential L.A. band, sang about the emigres who made their way to California:

She came from Providence

One in Rhode Island

Where the old-world shadows hang

Heavy in the air

She packed her hopes and dreams

Like a refugee

Just as her father came across the sea

When you are young, there is something liberating about living where your ancestors didn’t. The old-world shadows do hang heavier in the air in the east, not to mention in Europe. I’ve never been able to be in European cities, or even eastern American ones, without feeling slightly haunted, if not burdened. (I remember having an actual panic attack in Boston’s north end – the shades of my Puritan ancestors made me physically ill. It sounds woo, and it probably is, but it will be a while before I go back to Massachusetts to test myself.)

My family has been in California for 170 years, since the Gold Rush; my great-great-great-grandfather came for one kind of gold and found another. His son built the ranch on which my children frolic; black and white photographs of the ancestors smile down from the walls, next to the taxidermized remains of the buffalo my great-grandfather shot a century ago. These shadows do not hang quite so heavy. I walk the hills of the ranch and think that all my ancestors really want is for me to take care of the next generation and find whatever happiness I can. I am at home in those hills, home because I’ve known them all my life, and home because I have no more important job than to safeguard every square foot for my descendants.

Six years ago this month, I flew to Oklahoma to see about a girl. It was a romance doomed from the start, and after briefly convincing herself that my being older than her parents wasn’t a problem, time together forced her to concede I was much too old for her. Brittany dumped me, as gently as she could, during my visit, two days before my plane back to L.A. I couldn’t change my flight. Stuck with one wrenching Saturday in her little house just outside of Edmond, I couldn’t be near her any longer. Filled with the agony of a fresh heartbreak, I ignored the freezing weather and went out. I just needed to move.

I walked past the subdivisions, out onto the gray plains that made Auden shudder, and powered along a country road as the sky turned six colors of pink at 3:00 in the afternoon. I had never seen an Oklahoma sky in winter, never seen the plains grasses bend in an icy breeze.

A photo I took in Oklahoma of a landscape that took my breath away.

I texted she who was now my ex: “I think this is the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen.” Brittany texted back, “Are you okay? Are you drinking?”

Brittany had been dazzled by the beaches and Beverly Hills when she visited me, because they were new to her. I was equally enraptured by the Southern Plains in early winter because they were new to me. There’s a lot to be said for falling in love with what one has never known. Elsewheres can be equally marvelous, be they grand foreign cities or a field of Indiangrass under a gloriously dull sky.

I’ve slept in a suite at the Georges V in Paris, and I’ve slept on a filthy cot in a San Benito County jail cell, and both places seemed equally strange to me. I’ve been in more than one grand hotel, and in more than one jail, and none of them ever seemed quite where I belonged. Sometimes, the way I figure out what home feels like is to go to where home very clearly isn’t.

When I drive home to mama’s, back to the little cottage in which I grew up, I will come down Ocean Avenue, the main drag of Carmel. I will make a left turn onto Camino Real, and without having to think about it, I will immediately pull onto the right side of the street, to avoid a large bump. It’s been 40 years since I learned to drive, and the bump was old then; Camino Real has been repaved half a dozen times since, but that lumpy ridge of asphalt has stubbornly remained.

Home is where that swerve to avoid that ridge happens unconsciously; I could no more drive straight down Camino Real between Ocean and Seventh than I could burst out in conversational Mandarin. I suppose that’s true of most of us: the place where you are from is the place where you know which railing is loose, which tree the motorcycle cop hides behind, and, like my manager Sergio, which street marks a boundary you cannot safely cross.

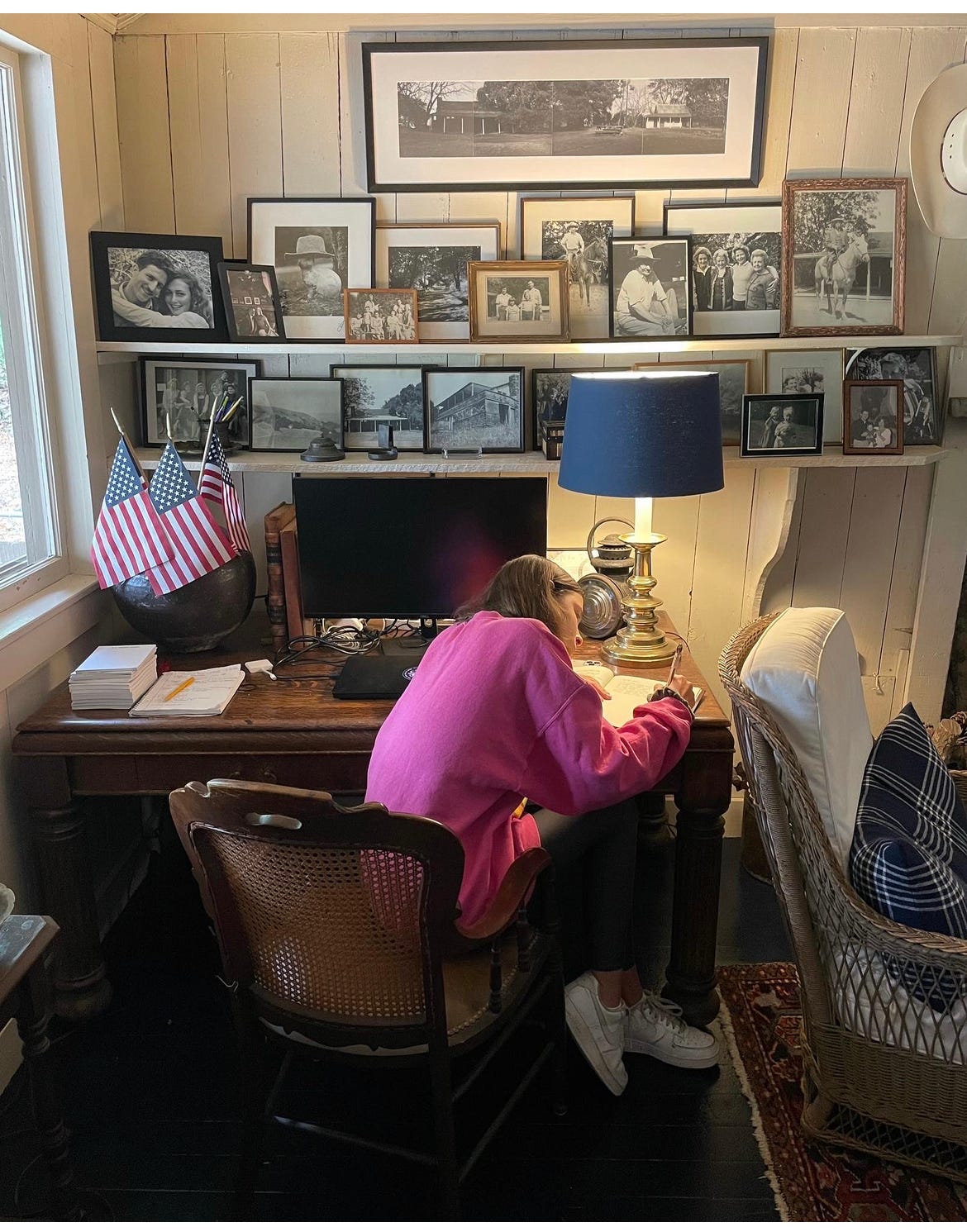

My daughter writes in a ranch book under the eyes of the ancestors. She says she feels at home here.

Merry Christmas, Hugo! I think we’d all like to know who the bunny in the hat is! Take care and have a terrific time with the family.

Thank you for a lovely read... Sorry it ended. Wishing you all a lovely happiness filled Christmas and a New Year filled with peace, love, lots of laughter and enough of everything else that's needed.