I Didn't See Babygirl but I'm Writing About it Anyway

Yesterday, I posted a plea on Facebook: “Please don’t let me write about Babygirl without having seen it first.”

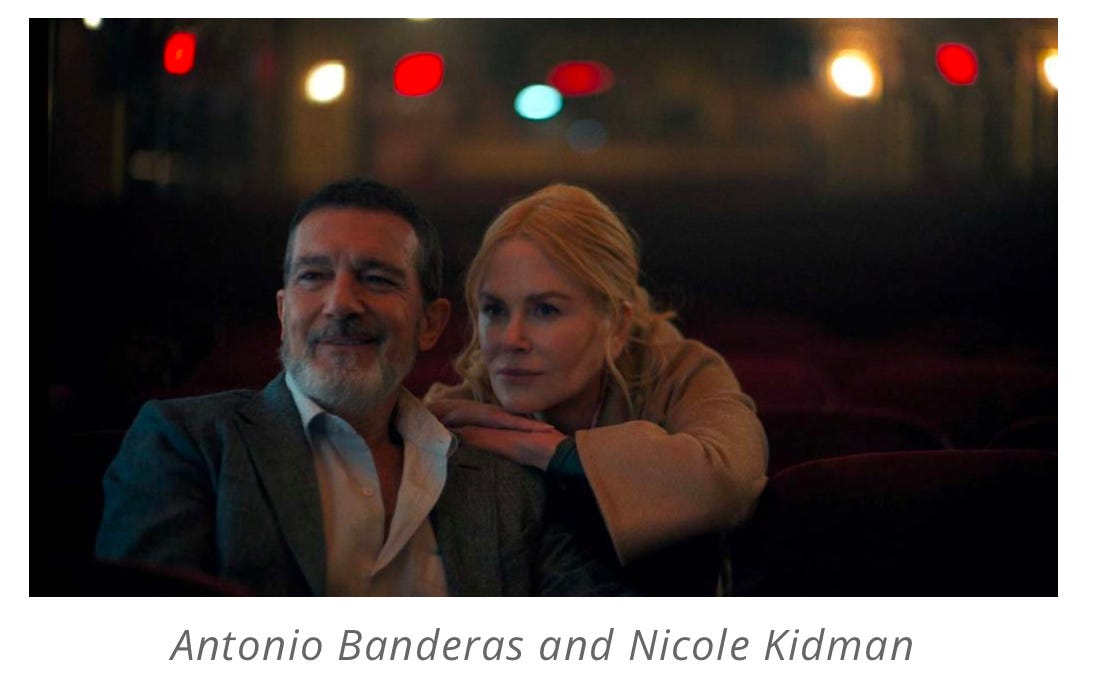

Babygirl is in theaters now. Starring Nicole Kidman, I gather the film tells the story of a middle-aged married woman, a successful corporate executive who has an affair with a much-younger employee, played by Harris Dickinson. The man she cheats with is her professional subordinate, but is sexually dominant. The wife, played by Kidman, finds deep pleasure in submitting — and this is a pleasure her husband apparently cannot give her. The husband who cannot deliver what his wife longs for is played by Antonio Banderas — a still-handsome 64 and a veteran of many a “sexiest man alive” shortlists over the past three decades. (Clever casting, I presume. Charming, great-looking, Spanish and eager to please? The assumption is that’s every woman’s dream, and the plot point that even Antonio freaking Banderas turns out not to be “enough” is a pointed reminder that we harbor a lot of superficial illusions about women’s sexuality.)

All this I have gleaned from the trailer, because here I am doing what I said I shouldn’t: writing about a movie I haven’t seen. A friend commented beneath that Facebook post that it would be unwise for me to say anything publicly about Babygirl. Cancel culture may not have the terrifying power it possessed five or six years ago, but no one wants to hear what an infamously problematic, fifty-seven-year-old straight man has to say about a film designed to explore women’s sexuality.

From 2010-2013, I had a weekly column for Jezebel. I was already middle-aged (43) when I started writing for that celebrated feminist website, and I was (obviously) a man on what was then an almost-entirely female staff. Over the course of three years, I wrote more and more often about sex. My editor and I both noticed the obvious: columns about sex got more hits than those about politics or pop culture. One gives the public what they want — or what they despise. To Jezebel, that was a distinction without a difference. If people click on something out of curiosity or out of outrage, the metric is the same. My three most-viewed posts ever were (in order) about “facials” (not the treatment you get at a spa), “pegging,” and why older men were sleazebags for pursuing younger women.

When I confessed my infidelities with my (much younger) students, I didn’t just spiral into professional and personal destruction. I also became the poster boy for the sad truth that male feminists are sanctimonious hypocrites who use progressive politics to get women into bed. I disappointed a great many people by embodying the stereotype. (My editor at Jezebel has never forgiven me for making her look a fool. I understand her position.) I have spent many, many years trying to rebuild a life, a career, and a reputation. The general view among my old friends is that my rehabilitation is impossible; among my newer companions, it is that rehabilitation may be viable, but it will be contingent upon staying away from the topics that made me infamous.

I am doing an excellent job of staying away from actual sex. I’m closing in on two years of celibacy, with no end in sight, and I am content to keep it that way. I am not doing quite so well in staying off the topic of sex. Some of that temptation is because it is familiar territory. Some of that urge is rooted in my own need to revisit past trauma. Sex work as a teen left permanent emotional (and a couple of physical) scars I am still struggling to understand. My affairs with my students destroyed my career, nearly took my life, and shattered my children’s worlds. The shame is with me every day. To swear off writing about sex, or confine it only to unpublished journals, is a painful but presumably necessary restriction.

Money is tight, and I don’t need to spend $20 bucks to take myself to see Babygirl. I don’t need to write about it either. I can point out that we’ve had a half dozen movies this year about older women having affairs with younger men, and that almost all the commentary about those films is being written by women. It is not just that no one wants to hear what Hugo Schwyzer, Disgraced Male Feminist (tm) has to say about this movie. It’s that no one wants to hear what any older man has to say on the topic. Presumably we’ll grumble. Presumably we’ll lament. We’ll moan that men like the character Banderas plays are good providers, faithful and eager to please the insatiable and the ungrateful.

That is not, in fact, the post I would write. If I were going to write about this movie I haven’t seen but whose plot points I have digested online, I’d argue that perhaps husbands should think of sexuality in terms of Venn diagrams. There’s a circle for my sexuality, and one for yours, and a third for what is shared. Yet that third overlapping circle doesn’t encompass everything. If I were writing about Babygirl and other films that explore this theme, I’d probably share that famous Rilke quote on marriage (from his Letters to a Young Poet):

A merging of two people is an impossibility, and where it seems to exist, it is a hemming-in, a mutual consent that robs one party or both parties of their fullest freedom and development. But once the realization is accepted that even between the closest people infinite distances exist, a marvelous living side-by-side can grow up for them, if they succeed in loving the expanse between them, which gives them the possibility of always seeing each other as a whole and before an immense sky.

Polyamory and swinging are one way of dealing with the “infinite distances” that exist between even the closest people. They are one way of allowing for “fullest freedom and development.” Another way, and perhaps the more… elegant… path… is to learn to accept and even love a gulf that cannot be bridged. A gentleman might accept that a part of his partner will always be a mystery to him. He might even accept that she might only be able to share this mysterious part of herself with someone else, someone with whom she shares none of the domestic comforts and obligations that form the foundation of their excellent marriage. He might wish it were otherwise, and smile ruefully that he cannot be all things to his bride — and then remind himself that he has his own impulses and fantasies that he cannot imagine sharing with the woman with whom he has built this magnificent life. He might decide that there’s a difference between love and enmeshment, between fusion and devotion. He might even decide that “don’t ask, don’t tell” functions not just as concession to frailty but as a policy of profound generosity. “To let the mystery be” is a discipline. Perhaps it’s one more of us should cultivate.

My friends to my left don’t think I’m qualified to say these things. My friends to my right think I would do well not to make such concessions to sin. All sides would probably prefer I have nothing to say about this controversial film I have not seen. We are who we are, though, and once I need to write about something…. it tends to happen.

I'm not in either camp, Hugo, though I veer wildly left. Meaning I continue to think you have a great deal to say and say it in a far more interesting way than much of what I read about the topics you have proven yourself to be adept at.

I take that I am one voice in the wilderness, but I do genuinely wish that whatever demons and barriers keep you from returning to the writing you do so well, would resolve.

While I understand the ire and and rejection from the feminist camp you once occupied, I see much of value in your perspective, "hypocritical male feminist" or not.

I, and I believe many others, would like to hear more once again on these and other subjects that cross your path and mind.

"He might even decide that “don’t ask, don’t tell” functions not just as concession to frailty but as a policy of profound generosity"

I love that.

Glad you wrote about it. I just published the one I was talking about on Facebook that included a paragraph about it, too, despite also having not seen it yet, lol.