Is a Gentleman Just a "Self-Effacing Doormat?"

It’s my birthday week, and I’d sure like to get to 85 subscribers by Saturday. I’m only three away. If you’re able, and you’d like additional content available only to those with paid subscriptions, I’d so welcome your support. And if you can’t buy a subscription now, please do make sure you’re signed up for the free content that comes regularly as well!

The (modern) definition of a gentleman today more or less boils down to “Be a schmuck!”

So claims Aaron Renn on his blog, the New Masculinist. Renn, with whom you are probably not familiar, is a right-wing author and pundit whose chief area of interest is providing love and life advice to young, white, disaffected Christian men. (Please read through his archives if you possess a high tolerance for chauvinism and certainty. The dude has a reliable grift, and to keep with his use of Yiddish, I respect his shtick, even if it’s nonsense.)

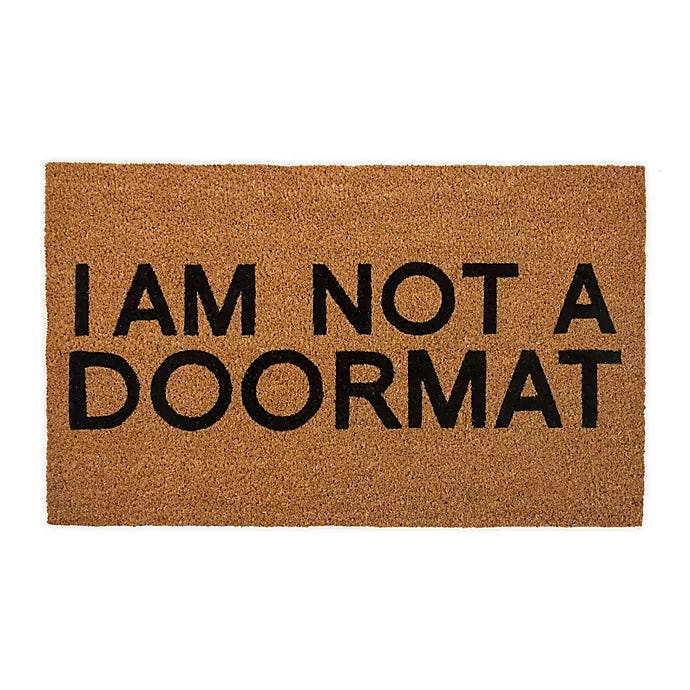

Renn last week revisits one of my own favorite subjects, the WASP ideal of the gentleman. He demolishes it as a useless, even dangerous model for male behavior. Renn accurately identifies self-sacrifice as central to the gentlemanly ideal, denouncing “the idea of continuing to play by an old set of rules while everyone else is playing by a new and different set.” This is a recipe for defeat, he says; the modern gentleman is nothing more than a “self-effacing doormat.”

Reading through the lines, Renn is arguing that Donald Trump’s boorishness is a better model for young Christian men than Mitt Romney’s commitment to decorum. For Renn, the essence of gentlemanliness is an acceptance of, even delight in, inevitable defeat. Young men want to be told it’s okay to win at any cost, and to use any tools in their arsenal to do so. It’s not just that the unrestrained ids of the Matt Gaetzes and Donald Trumps of the world are necessary evils to be tolerated by conservatives eager for victories, it is that they represent a kind of bold rapacity deserving of imitation.

Renn would find much in my own writing to back up his claim that gentlemen relish being doormats. In December, I wrote about my own family’s admiration for losing with style:

As my grandmother put it, "be the gentleman who jumps the net” -- a reference to the old tennis tradition, generally abandoned, wherein the losing player leaps over the net into the court of the winner to shake his hand, grinning all the while. I learned to "jump the net" when I lost the election for home room vice-president in seventh grade: I learned to jump the net when I didn't get the part I wanted in the play; I learned to jump the net when the girl I liked wanted another boy instead.

Jumping the net is not about pretending one didn't want to win. In a tennis match, everyone knows the loser tried their best and still came up short -- it's how you handle public defeat that defines your identity. Losing, of course, became character-defining: a gentleman was not defined by his victories or successes, because they revealed nothing -- it was how he responded to humiliation and crushing disappointment that would show his breeding and his true nature.

If someone cheats you out of some money, let it go. If someone cuts you off in traffic, swallow hard and let him. If your girl says she doesn't have feelings for you anymore, you may weep and you may be heartbroken, but you wish her well. (Extra points if you warmly shake the hand of her new beau.)

The KEY to being a gentleman when it comes to handling disappointment is to avoid public displays of anger. Crying -- at least a little -- is just fine, particularly if one mutters "I'm so terribly sorry" while one weeps. Raging -- "like a drunk Irishman", to use a bigoted old family phrase -- is the worst thing one could possibly do. (It's why my family laughed when journalists called Brett Kavanagh a WASP -- his intemperate, if perhaps understandable display of rage before the Senate was the least WASPy thing ever.)

I’ve added the emphasis. Renn might read this and say, “Nice story—thanks for explaining why you’re a useless wimp.”

I’ve been very candid about my own mental illness, and I’ve written frequently about the WASP ideal. It wouldn’t require that one be particularly unkind to point out that the brand of “gentlemanliness” I defend is inextricably bound up with my own trauma and darkness. We all have to guard against the tendency to make virtues out of our defects, and for someone who is defined by overwhelming self-loathing, it makes good sense to celebrate “self-effacing doormat-hood” as an ideal.

If you ask me when I felt most like a gentleman, I will tell you it was the day I resigned my position with the college. I knew I was blowing up my life, and I might never recover – and I decided to play the whole thing with a warm, jovial insouciance. A gentleman goes to the gallows whistling a merry tune, and tells a funny story to reassure the hangman. He knows that that sort of end is his destiny, and he accepts it with good cheer.

Dude, that’s pathetic. I hope you get the help you need. (I can hear Renn’s reply in my head.)

That’s my story. But it is absolutely not what I want for my son, or for any other man. My personal story may be alternately pathetic, or tragic, or just a sheer dumb waste, but I do not want it to be exemplary. Renn is right: there is a certain kind of gentlemanliness that has no vocabulary for enduring success. If you feel most at home being a doormat who loses things, you will be trod upon and you will suffer endless reversals. It’s hard for therapists and spouses to talk you out of fulfilling the prophecy to which you are so tenaciously, stubbornly attached.

There is another aspect to what it means to be a gentleman. I know it even if I can’t embrace it; Renn should know it, and pretends not to see it. It is an ideal that I want my David and other young men to follow; it is one that permits, even enables success and happiness.

The gentlemanly ideal is defined by service. It charts a middle course between uninhibited greed and decorous self-loathing, trusting that there’s a lot of open water between those two extremes. It (correctly) points out that self-hatred is as much a selfish indulgence as is unchecked ego, as both self-loathing and excess pride make it hard for you to successfully address the deep needs of your loved ones and the larger world.

It is true that a gentleman accepts defeat well. But your correspondent and Elizabeth Bishop excepted, it’s a mistake to make an idol out of losing. It is possible to win at many things, and keep one’s promises, and enjoy oodles of success, and still hold on to one’s manners. Kindness and toughness are not antonyms, and neither are victory and grace.

Kipling is very much out of fashion these days (to put it mildly), but his “If” continues to point to an enduring aspect of the gentlemanly ideal:

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same…

A gentleman meets success and failure with equanimity. The fact that I’ve twisted that ideal to valorize Disaster over Triumph is my own mistake, just as Renn’s assumption that that same ideal will invariably lead to Disaster is a perverse misreading of what it means to be well-mannered. You can win without being a craven boor, Trump’s vile example notwithstanding. (One might point out that a refusal to accept obvious defeat is not, in fact, the same as an actual triumph.)

A gentleman recognizes that service to others does not require suppressing all his desires. His ambitions, his honesty, and his ardor can and do bring joy to other people. Folks tend to get annoyed when you assume that they can’t handle your truth, and you try and protect them from your own excellence. It’s easy to cross the line from being of service to being patronizing, just as it is easy to cross the line from being honest to being cruel. Part of being a gentleman is doing the hard, but ultimately deeply satisfying work of finding the balance.

Many years ago, I was a distance runner. I was never especially fast, but I hung out and trained with those who were. We ran marathons and ultras together, and we did track work together. In 1999, when I was at my fittest, I did a 10K in Baldwin Park with Joe, one of my good friends from the running club. We paced each other the whole way, staying on target with our goal to get under 39 minutes. We had agreed that when we reached the final 200 meters, it was each man for himself.

I had done these final kicks with friends in races before. I never won. If my friend was faster than I was, my best efforts were for naught; if I had the better kick, I would always find a way to let up at the end. Once, I let it be too obvious that I was holding back, and a friend called me out for not trying my hardest.

In the Baldwin Park race, Joe and I both accelerated at the appointed mark. I pushed as hard as I could, my brain fiery, my chest tight, red dots swimming before my eyes. Joe fell slightly behind. He’ll get me in the last 50, I thought. But Joe didn’t, and I didn’t let up. I came across the line first, my buddy two steps behind. We both doubled over, nearly collapsing. I looked at the time on my watch. It was a personal best. I hugged Joe. “Great race, man,” I told him. “You pushed me so hard.”

“You had me at the end, Hugo,” Joe said. “I didn’t have an answer for you.”

I felt the “I’m sorry” rise to my lips. Joe saw it, raised his eyebrows, and waited. I swallowed the apology. Joe grinned. “That’s it!” He cried. “Own the damn thing!”

Own the damn thing. It was difficult, but wondrously good to win. My manners didn’t disappear in victory. I bit back the apology for having come in ahead of my friend, and rather than insult his speed with my regret, I celebrated. What an epiphany it was; I could love someone and still beat them at something without losing myself.

It was a fleeting revelation in my own life, rarely repeated. It need not be that way for anyone else.

____________

The song I had on repeat while writing this is by L.A.’s own Leslie Stevens. This single made many country critics’ Ten Best lists in 2019. It’s about grieving a loved one’s suicide, and for those of us who live with a constant urge to self-harm, it’s a fierce reminder of how much damage our departure would cause. The final image of the dead leaving behind “unopened gifts under a cut-down tree” is deeply haunting:

Still there's something in the feeling

That love must be a light

For I can feel it

Even in the darkness of this night

We're all imprisoned by ourselves

Though there's suffering in sight

Still love comes near and we're free

You left so many gifts under that tree

Unopened gifts under that cut-down tree