Many years ago, I served on the Vestry of my local Episcopal Church. The rector, a great believer in personality tests, liked to start Vestry meetings with icebreakers. Before we got down to the business of lamenting the A/C bill, debating the need of a new roof, or championing the consecration of gay bishops, we’d start by answering a question designed to get everyone relaxed and talking.

Memorably, Rev. Ed started one Vestry meeting by asking each of us around the table to name our favorite Beatle. We were a “seeker sensitive” church, and so as you might expect, about half of us said George, and the rest split evenly between John and Paul. The rector went last, and with a great grin, said that most of the rest of us were too young to appreciate Ringo. In time, the rector remarked, many of us would decide that the drummer born Richard Starkey was, after all, the one to whom we felt the most deeply attached.

I laughed. I figured it was sufficient progress that I had gone from worshiping the brooding, snarling John Lennon in my teens to admiring George Harrison -- the “quiet Beatle “-- in my 20s and 30s. To my younger self, Paul McCartney was way too off-puttingly earnest and unseriously cute. Ringo was a bit of a joke, surely, the least talented of the lot, an accidental Beatle, the bemused, bumbling winner of pop culture’s biggest ever lottery payout. (George was deep, man. Like me.)

Ed, the old All Saints rector, was right. I’m 56, and Ringo has indeed become my favorite . My younger self saw Ringo as an amiable lightweight; in late middle age, I see so much genius disguised in the insubstantial. I’m aware that only lately has Starr been acknowledged as one of the greatest pop drummers of the last century but I’m not paying tribute to his skill with the sticks and the skins. I’m struck by his fierce, irrepressible joy.

Victoria and I went to see Ringo and his “All-Starr Band” in Long Beach last night. The All-Starr band consists of an ever-changing lineup of other aging rock stars. Ringo’s tours give men in their late 60s and 70s a chance to play to packed houses still, singing the hits that made them rich decades ago. These guys might not be able to sell out venues on their own, and they might not have the stamina to headline a full set. Working together, trading songs, and taking breaks, they rail on against the dying of the light together four nights a week, with Ringo the omnipresent, lovable, self-deprecating ringmaster.

The All-Starr lineup on tour in 2023 features Edgar Winters of the eponymous group, and surviving members of Toto, the Average White Band, and Men at Work. Ringo banged his kit and offered harmony to the songs for which his All-Starrs are best known. Last night, the mostly Boomer audience sang along to “Rosanna,” “Down Under,” “Pick up the Pieces” and other classics that topped the charts no later than the first Reagan Administration.

Ringo sang a few of his own solo hits: the aching “Photograph” (a song co-written with George Harrison), and the best-known song he penned by himself, “It Don’t Come Easy.” Outwardly, so much seems to have “come easy” to Ringo, his life less touched by tragedy and tempest than those of his more celebrated bandmates. I’m old enough now to know better. The longer you live and thrive, the less chance there is that you are an accidental survivor, and the greater the likelihood that your success is a consequence of exceptional talent mixed with relentless work. Ringo’s brilliance is that, like the greatest of dancers or athletes, he makes the sublime appear effortless. When you can’t see the sweat nor sense the calculation, you might underestimate the genius, but it is still there.

Ringo sang “Yellow Submarine,” the Beatles song with which he is best associated. I wondered, as I sang along, how many millions of others have sung those same words, and I wondered how many of them felt as moved by the ridiculous.

(As a sidenote, there is one of his old hits Ringo never performs live anymore: “You’re Sixteen.” Just as the aging Rolling Stones removed “Brown Sugar” from their setlist several years ago, Ringo has read the room in the #MeToo era. We are in a prudish and protective age, and odes to 16-year-olds who “come on like a dream” lead to glares and pearl-clutching. Perhaps that pendulum will swing again, but probably not before Ringo takes his final bow.)

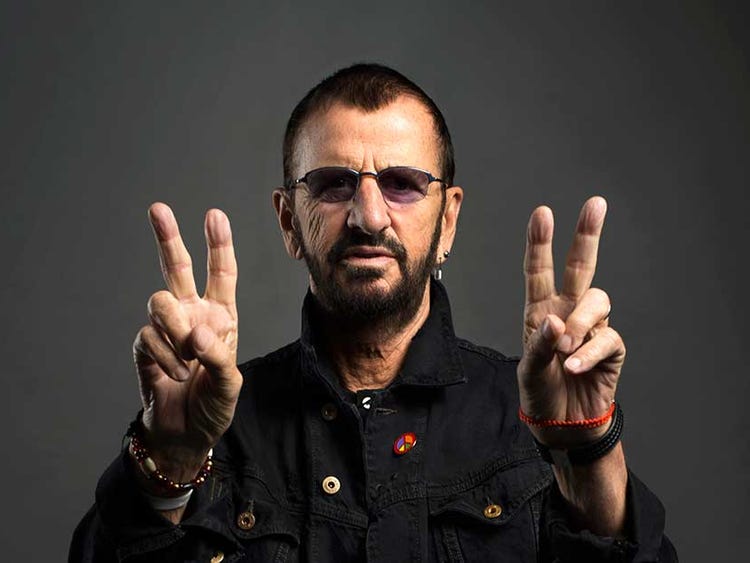

“Peace and love,” said Ringo, over and over again, raising fingers on both hands into that familiar V. “Peace and love,” the crowd shouted back, making the sign back to him. After one such exchange Ringo added “I really mean that, you know.” The crowd cheered.

I wondered, for a moment, how many of those people raising their middle and index fingers together for Ringo leave the middle finger standing alone for those they despise. How many in the aging audience are cable news junkies like most of my older relatives? How many spend hours each day so angry they could spit at evil Republicans, or at Deep State Democrats? How many think America is beset by existential threats for which cries of “peace and love” are no solution at all? How many think that put into practice, “peace and love” represent acquiescence to evil?

It is fashionable for activists on both left and right to insist that “Now is a time for choosing,” and to declare “We are on a war footing.” Trans activists are coming for your children! Ron DeSantis is coming for your libraries! Donald Trump is coming for your democracy! Big Pharma is coming for your genes! White supremacists have infiltrated our military! The Chinese Communist Party has infiltrated our social media! George Soros has infiltrated our courtrooms! There are Proud Boys in the shrubbery! We must boycott this! We must ban that! We must fight fight fight, for the barbarians are at our very gates! Great God, they’re in the walls!

(Some of you probably believe some of those things. Some of you are probably right about the things you believe. None of you believe all those things, I don’t think, but in two thousand twenty-three, nothing would surprise me.)

At the close of the concert Ringo and the six men of the All-Starr band stood shoulder to shoulder at the front of the stage. They took their bows, drank in the applause, and then these seven -- with a combined age of half a millennium – sang the chorus made famous by John and Yoko: “All we are saying is, give peace a chance.”

The All-Starrs sang the line three times, 27 words in total, their faces glowing. It was much more solemn and beautiful than all that had come before it; it was liturgical in its power. The last “chance” echoed; Ringo flashed the V once more, and arm in arm, old lions skipped off stage into the good night.

The house lights came up. I saw many a tear on many a wrinkled face, and anyone who looked would have seen my face wet as well. Two thousand of us, the vast majority Medicare-eligible, made our way down the theater’s stairs, clutching the railings, choosing our footing carefully, leaning into loved ones, humming the tunes we’d all just heard.

But. What does it mean to sing “Give peace a chance?” What does it mean to shout “Peace and love” back at a charming old man for whom those words are a defining slogan? Are they abstractions? Is saying “peace and love” like shouting “immortality,” a declaration of a desire for a nice thing that is sadly unattainable? Is it a reminder of a long-abandoned naivete that is nonetheless pleasurable to recall? Or is it a method, a praxis, a discipline? Is it -- just maybe --something we are called to live out, and not just something we are invited to desire?

Maybe Ringo’s just a rich, old, happy-go-lucky rock star as devoid of moral heft as he is of gloom. Maybe (probably) John and Yoko were insufferably self-regarding. Maybe “Give Peace a Chance” has all the weight of a group of earnest fourth graders singing “Santa Claus is Coming to Town” at the elementary school holiday show. It’s not a real charge to keep. It’s a pretty lie.

Or maybe it matters how you drove home from the concert, and whether you let other drivers into your lane. Maybe it matters how you react when the talking heads come on your television or Twitter feed to stir up your outrage and your anguish. Maybe “peace and love” are not an invitation to withdraw into meekness, but a call to be kinder in your fighting. Maybe it’s a slogan asking you a question: how many concessions will you demand from others before you give them peace?

I know what “peace and love” mean to me. I am deeply curious about what they mean to others.

I’m glad I finally got to see my favorite Beatle.

Beautiful and truthful sentiments, Hugo.

I feel peace and love after reading this. Thank you.