"Nothing is More Cruel than Righteous Indignation:" In Praise of Defense Lawyers

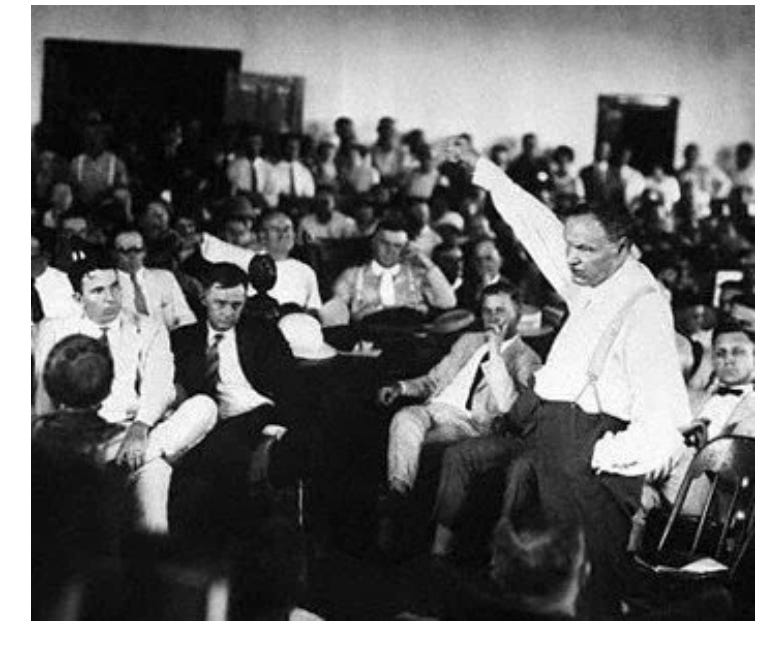

(Clarence Darrow in court, 1920s.)

I am always suspicious of righteous indignation. Nothing is more cruel than righteous indignation. To hear young men talk glibly of justice.

Who knows what it is? Do I know? Does Your Honor know? Is there any human machinery for finding it out? Is there any man can weigh me and say what I deserve?

Can Your Honor? Let us be honest. Can Your Honor appraise yourself and say what you deserve? Can Your Honor appraise these two young men and say what they deserve? Justice must take account of infinite circumstances which a human being cannot understand.

I was 11 when I first read Clarence Darrow’s closing argument in the Leopold and Loeb case. I was at my desk in my bedroom, and I leapt up, ran down to where my mother was grading papers at the dining room table, and insisted on reading extended portions of Darrow aloud to her.

“I know what I want to be when I grow up,” I told her. “I’m going to be a criminal defense attorney.”

Like many kids on the cusp of adolescence, I had long been interested in true crime stories – and the problem of evil. Deep down, I suspected I was bad, and so I found comfort in reading about other people who had done genuinely terrible things. I campaigned against the death penalty starting in fourth grade, writing my first letter to the editor of the Monterey County Herald to protest the execution of Gary Gilmore. “Everyone has good inside them, even if it’s hidden,” I insisted, “Everyone deserves another chance.”

Long before cancel culture, and long before I lost my own career, I was committed to trying to defend those whom the world in its wisdom declared indefensible. Justice must take account of infinite circumstances which a human being cannot understand – I quoted that line every time someone around me called for a long prison sentence, or the death penalty. I cheered when someone got a light sentence, or was acquitted altogether. I was nearly beaten up at school after I expressed surprise and happiness that Dan White was convicted of manslaughter, rather than murder, for shooting Harvey Milk and George Moscone at San Francisco City Hall.

I know a great many people who dreamed of being lawyers so they could defend the innocent. It is a noble thing to defend the innocent, and only a fool believes that only the guilty end up on trial. We have a long and ignoble history of prosecuting the poor, or people of color, for crimes they did not commit. It is urgent and necessary that we break that cycle.

The protection of the innocent is not the only reason we have defense attorneys.

I was certainly open to defending the innocent, but far more excited at the prospect of defending the guilty. The idea that even those who have been caught red-handed, or who have confessed, deserve a vigorous, creative, and impassioned defense still strikes me as perhaps the most extraordinarily insightful and generous component of our entire legal system. I wanted to be like Clarence Darrow, finding a way to convey the humanity and vulnerability of those whom the world had declared to be monsters. I wanted to be the one to make people second-guess their own certainties. Nothing is more cruel than righteous indignation, Darrow said – and I wanted to dedicate my life to talking people out of that greatest of cruelties.

It didn’t happen for a host of reasons. I became a teacher instead, and a cheerleader for defense lawyers with guilty clients. (I was thrilled when OJ got off, and over the moon when somehow, Casey Anthony’s team pulled off their famous miracle.) In a small way, I have done what I set out to do: in the age of swift and reckless reckonings, I am still pleading for leniency, for humility, for 97th chances, and for seeing the good in the monsters of our age. I just do it on Facebook instead of a courtroom, and though I am not effective in changing minds, I plug away nonetheless. Is there any man can weigh me and say what I deserve?

This brings me to the Derek Chauvin trial. I didn’t watch it, but from what I gather, the defense was inept. Admittedly, they didn’t have much to work with, and the video evidence was impossibly damning. Given the near-certainty of a conviction, I would have urged Derek to take the stand in his own defense, prepare him for a brutal cross-examination, and give the jury a chance to see him as more than a smirking cretin who extinguished another man’s life. When you have the facts, argue the facts; when you have the law, argue the law; when you have neither, argue the humanity of the defendant. The work of the defense lawyer is to argue against certainties, to appeal to humility, to ask each of us if we are so omniscient that we can weigh another human and say beyond reasonable doubt what that man deserves.

Perhaps the defense will do a better job when it comes to sentencing.

When I was a boy, it was my friends on the right who mocked defense lawyers. The conservative columnist George Will famously quipped that “In our system, one is innocent until proven guilty; to the liberal, one remains innocent even after being proven guilty.” (I thought it rather a compliment, but apparently not?)

Today, it is my lefty friends who are angry at those who sit and stand with the accused. Why do we even need a defense in the George Floyd trial? We all saw what Derek Chauvin did! Why do we allow someone to attempt to explain the monstrousness of Harvey Weinstein? It’s too painful to victims to sit and listen to the lies and distortions defense attorneys always peddle. Can’t we just hear what the victim had to say, and let that be enough?To the truly Woke modern mind, a capable and creative defense is the unnecessary re-traumatizing of the already victimized.

And yet. The genius of our system is that it should be immensely difficult to convict someone of a crime. The suffering of the victim may be real, but suffering alone is not sufficient evidence to deprive the victim’s tormentor of his freedom. The burden rests on the prosecution to prove that what is alleged was in fact done – and the system only works when the accused has a team ready to challenge the certainties that the prosecution will peddle.

Some of us are content to live with doubts. Others fear doubts, and long for certainties. Our criminal justice system must dispense justice, but it must do so with caution, with humility, and only after every last reasonable doubt has been raised and considered. Perhaps some people really do deserve to be locked away; my heart belongs to those who devote their lives to arguing that perhaps, just perhaps, we do not see what we think we see.

My heart belongs to thosewho find the flower of complexity growing in the garden of the obvious.

My heart will always be with those who argue that nothing, nothing is more dangerous than righteous indignation.