One Week as a Deke

In the fall of 1985, my freshman year at Berkeley, I rushed Deke. Put in more basic terms, I pledged Delta Kappa Epsilon, the fraternity to which my mother’s father and his father and a large assortment of uncles and male cousins had belonged.

I did not especially want to be a frat boy, mostly because I didn’t like all-male spaces. (As today, more than half of my good friends then were women. Male friendships were and are happy, rare exceptions to a general rule.)

I already knew I had a drinking problem, too, and was afraid the Dekes would make it worse.

My family pressured me to give it a try. More to the point, they pressured the fraternity. The chapter and the national organization both got phone calls and letters from my family the summer before I went to college. A week before I moved up to Berkeley, I got a casual phone call in return from a rising senior in the house, mentioning that the brothers were looking forward to meeting me.

The moment I walked into the Deke house, it felt like a bad fit. My clothes were wrong, my body was wrong, the whole feel was wrong. At the first rush event, I thought the brothers were too handsome, too preppy, too intimidating. I was sure they thought I was too nerdy, too awkward, too soft around the middle.

I tried to comfort myself with reminders that according to my mother, my grandfather had also often felt out of place, but he had found a home in this very house. (And by house, I mean both the physical Craftsman structure and the organization.)

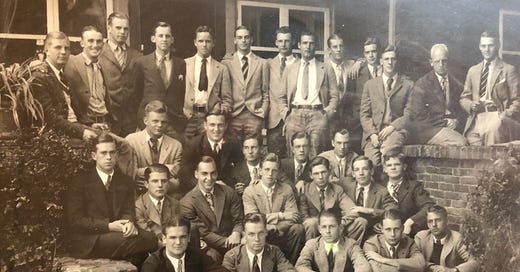

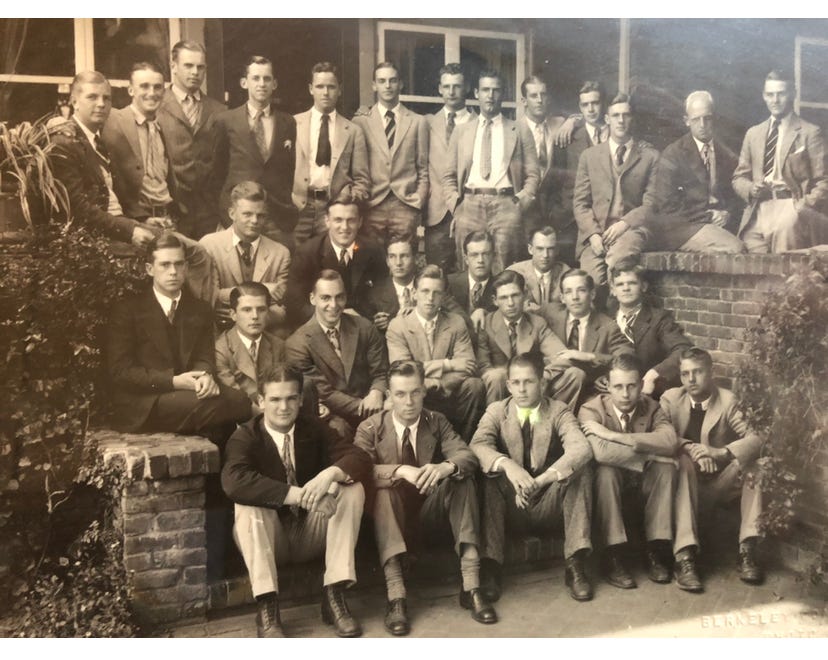

I have a photo of him with his fraternity brothers, taken in 1927, and my grandfather looks a little less cheerful than the others. Jerry Bishop, his future brother-in-law, seems to be cheering him up. (My grandfather is second row from the bottom, third Deke from right. My future step-grandfather, who will marry my grandmother after my grandfather dies, is in the third seated row from bottom, second from left. Two other cousins are in the photo.)

To my considerable surprise, the Dekes extended a bid to me. (There was another term for it, one I can’t remember).

My aunt, the chief cheerleader for me to join Deke, was ecstatic when I told her. My friends — including my high school girlfriend — were skeptical at best, scornful at worst. “This isn’t you,” they said. “They’ll be awful to you.”

A week after I pledged, one of the senior members of the house asked me to take a walk with him. We strolled down Piedmont Avenue on a Sunday afternoon.

We took you on obligation, he said, gently. We took you because of your family connection. And we only took you, he added, because we were sure you didn’t really want to join us anymore than we wanted you.

You’ve done your bit for your family, he said. Now , I’d like you to consider taking the best way out for everyone, including yourself.

He said all this effortlessly, in between greeting by name virtually every last student we passed on the street. I’ve always imagined he turned out to be one of those people who fires others for a living, delivering bad news in a way that is digestible, irrefutable, and mercifully quick.

This brother whose name I can’t remember — but who was tall and blonde and played water polo — told me that everyone would understand if I dropped out at this point, that my family would accept my decision, knowing that at least I’d tried.

I felt equal parts humiliated and relieved.

Most of the conversation I’ve reconstructed. This was 36 years ago. I do remember precisely one thing he said, right before he turned to me, grinned warmly, shook my hand and wished me luck.

“Our families only want the best for us. But sometimes, we’re not really who they think we are. You did the right thing, Hugo, standing up for yourself like this.”

I smiled. I will forever be in awe of his skill at ensuring that my separation from Deke would not only appear best for all, but presented to the world as largely my idea.

We parted. I went to a coffee shop, wrote a short letter of thanks and resignation on a piece of notebook paper, and walked it back to the Deke house. A quick round of slightly embarrassed handshakes, and the strange experiment was done.

Sometimes, we’re not really who everyone else thinks we are. It was a good lesson.