Online Friendship, Loyalty, and the Death of Dooce

I was 14 when I first read 84 Charing Cross Road. First a book, then a play, and finally a film (with Anne Bancroft and Anthony Hopkins), 84 Charing Cross Road tells the true story of a deep and touching devotion that developed between the American writer Helene Hanff and a London bookseller named Frank Doel.

In 1949, Hanff writes to Doel’s bookshop, looking for a rare volume. The volume is unavailable, but the correspondence soon moves on to other topics. Gradually, it becomes more familiar, then tender. Year after year the letters continue, as Doel and Hanff grow older and America and Britain transform. Theirs is a deep friendship, on the knife’s edge of romance, charged with profound affection. In 1968, just as Hanff makes plans to travel to England at last, Doel dies suddenly. She learns of his passing through, of course, a letter.

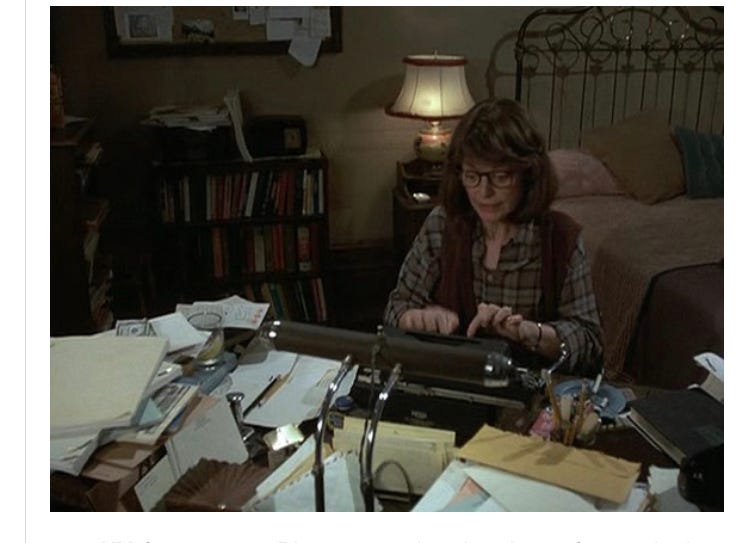

Helene Hanff (Anne Bancroft) writes to a man she loves but will never meet.

(The movie didn’t work for me, but the book is still a guaranteed tear-jerker.)

I started blogging 20 years ago. At first, only my parents read it. Then someone suggested I start commenting at length on other people’s blogs; if my comments were interesting enough, this friend said, these more famous bloggers would click through and start reading what I had written. It turned out to be so.

From 2003 to 2013, in fits and starts, I gradually became famous on the Internet. Not hugely famous, not a household name. Microfamous, maybe. Microinfamous, certainly. I started editing and writing at other websites away from my blog, such as the Good Men Project, Jezebel, and The Atlantic. In 2009, I wrote my first “viral post.” It was a strange thing to realize that over 1 million people had read (or at least, clicked on) something I’d written. Whatever that strange feeling was, I wanted more of it.

Most people do want more. We hunger to be to be seen – and even the smart ones among us (especially, maybe the smart ones) fall for the lie that being read or being recognized is the same as being known, loved, and affirmed. In 2011, I was at a conference in Atlanta, and I wanted to take a colleague out to dinner. I looked up a place and called to make a reservation. The hostess wanted my full name (and credit card) to guarantee the time.

When I spelled Schwyzer for her, I heard a gasp. “Wait. Do you write for Jezebel?” I said it was so. She squealed and told me she loved my columns. As you might imagine, I was the one squealing on the inside. I suspect she has forgotten me. I have not forgotten her. Stephanie was her name, and Stephanie in Buckhead made me feel famous.

I understood, of course, that the Stephanies of the world didn’t really know who I was. What was harder to understand is that the network of colleagues and friends I had cultivated over the years was also made up of people whom I did not truly know. Many of those people would turn away in disgust when I had my fall from grace. They felt betrayed that I had turned out to be something other than what I had represented to the world; I felt betrayed that many of those who publicly denounced me were those who had once asked for my help.

I learned a good lesson about online friendships. Sometimes, the people you meet are the Helene Hanffs to your Frank Doel; you never meet in person, but the loyalty is genuine and enduring. Those friendships tend to be rare. More often, your Internet friends are well-meaning, and they may even think they like you, but your camaraderie, to the extent that it exists, is deeply conditional in a way that “real world” relationships rarely are.

I muse on all this because a writer I admire, Thomas Chatterton Williams, has just had a familiar epiphany. TCW, as he is widely known, is a spirited and clever defender of classical liberalism. I have always enjoyed his writing. This past week, TCW offered a modest defense of Daniel Penny, the subway-riding Marine who held Jordan Neely in a chokehold until the latter died. (I suspect you have heard of this case.) TCW found himself in the middle of a firestorm – what we used to call, in the slightly more innocent late aughts – an “online takedown.”

In moderate anguish, TCW tweeted:

Williams took particular issue with a Daniel Torday, who had apparently once asked TCW for help and had now publicly turned on him. Williams threatened to publish all Torday’s past messages, asking for advice and assistance, in order to provide evidence of ingratitude. TCW apparently thought better of it, and I am glad.

Buried in my own Messenger and email archives are countless old requests and friendly chats with people who later denounced me. I would no more reveal the content of those messages than I would share a nude photo given to me by an ex. A gentleman doesn’t publicly reproach people who behave badly. Those who choose politics over friendship have shown themselves ignorant of the meaning of the latter, and that is arguably punishment enough.

Turning on one’s friends because they have said the wrong thing is not new. It happened in Savonarola’s Florence, in Robespierre’s Paris, in Stalin’s Moscow, in Mao’s Shanghai. It happens on college campuses and in woke newsrooms today. (Yes, friends, I recognize my own hyperbole. There is a difference, but smaller than you think, between professional ostracism and the actual guillotine.)

What makes it so stunning to TCW, and to me when it happened, is that we allowed ourselves to believe that courtesies given (and kindnesses exchanged and drinks shared) carried actual moral obligations. In an ideal world, we would never denounce in public those whose favor we had sought in private, even if those people turned out to hold inexplicable or reprehensible views.

We do not live in that world. I know that, and you probably know that, and TCW knows that now.

I said above that I started blogging 20 years ago. When I opened my first Blogger account in the summer of 2003, I had just learned that “blog” was a truncation of “web log,” itself a rather new idea. Back then, the only person I had heard described as a blogger was Heather Armstrong, better known to the world as Dooce. A pioneering “mommy blogger,” a master of the painfully honest confessional style, Armstrong committed suicide last week. I never met Armstrong in real life or online, but we had many friends in common. Her death, after a prolonged struggle with addiction, is heartbreaking.

Last summer, Armstrong posted a few things that were, in the minds of her critics, “anti-trans.” The venomous reaction wasn’t quite as bad as what J.K. Rowling has encountered, but it was not far off. Longtime friends denounced “Dooce.” Others, in a misplaced effort to be charitable, attributed her views to a relapse with drugs and alcohol. Leaving aside the substance of our intense contemporary debate about trans identity, we can agree that the discussion itself has become toxic. No one is allowed to ask questions; one is required to affirm or condemn without ceasing. Dooce didn’t play by those rules. Her erstwhile allies turned on her. Whether that led directly to her suicide or not I don’t know, but from bitter experience, I can confirm that being denounced by people you once thought were your friends is soul-scarring. It can indeed lead to thoughts of suicide.

There are only so many people we can meet in real life. The friendships we form online are meaningful, and perhaps in a few instances, as profound as what Helene Hanff found with Frank Doel. We can love people we’ve never met. The corollary to that is that to never meet is always to live with some kind of fantasy. We imagine sexual chemistry where there would in fact be none. We imagine that kindnesses exchanged in private messages amount to promises. We imagine that those who praise us have seen our truest selves, and that surely, if things get sticky, they’ll stand by us. If we believe these things, we set ourselves up for heartbreak. Thomas Chatterton Williams will survive this betrayal, as I survived my own feast of losses. Heather Armstrong was not so lucky.

Stephanie, the hostess from that Atlanta restaurant? She sent me a friend request on Facebook the day after we met. She ended up asking for help on an essay she was writing about feminism. She unfriended me when I fell. I blame her for none of that, of course. She was one of many who showed me the difference between fan and friend, between business contact and companion.

In the online age, knowing that distinction is a matter of life and death.