Promise me son, not to do the things I’ve done.

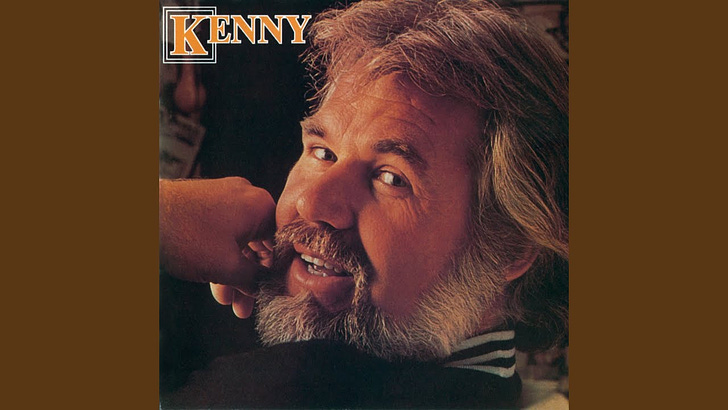

“Coward of the County” was a monster hit for Kenny Rogers in the fall of 1979, topping both the country and pop charts. I was 12 when I first heard it, and I secretly loved it, and was openly disdainful of it anyway, having just reached that tiresome age where a nerdy child feels compelled to dismiss anything too popular and mainstream.

Later, I’d admit the craft in the songwriting, and the genius in Kenny’s delivery.

The first time I heard it in the car with my son, he was five. I sang David the chorus, the words of an imprisoned ne’er-do-well father to his own young boy, begging the child to take a different path.

Promise me, son.

I sang the chorus again, and grinned at him in the rear-view mirror, letting my eyes water.

Not to do the things I’ve done.

I don’t want him to get thrown out of school for stealing when he’s 13. I don’t want him to start drinking at 14. I don’t want him to feel handcuffs on his wrists, feel the psych techs hold him still while the nurse jabs the Haldol or Ativan in his butt, or feel the self-loathing course through his twisted guts when he sees the crumpled face of a woman he’s lied to, yet again.

I want the family genetic lottery of the disease to miss him and his sister. I don’t want him to cut or burn his skin or hear things that aren’t there. I don’t want him to become an object of derision and disgust, an Internet footnote, a cautionary tale, a joke.

I want him to say “I love my dad, but he did a lot of foolish things, and I learned from them so I wouldn’t have to be too much like him.”

Walk away from trouble if you can.

“Coward of the County” is a country song, and country has rules, and one of the rules is that, in the end, it don’t matter what the daddy wants. The son will take from his father what he needs. And he will do at least some of the hard things his father did.

“Why are you crying, abba?” David asked, as I sang along that first night.

“Because it’s a song about us, bunny.”

David didn’t say anything. Then, as we neared the house:

“Can you play our song again?”

That was four years ago. I’ve been playing that song for him every week or two since, and it leads to more and more discussions as he grows and learns about the world.

He asks about when and where he can fight. His mother’s rule prevails: you are not allowed to start trouble, but you are allowed to finish it decisively.

He asks about the song’s theme of gang rape (a traditional, if not particularly feminist plot device), and reminds me of all he’s already learned about consent and respect for other people’s personal space.

He asks me about the times I’ve gone to prison, and though I explain that a night or five in county jails are not exactly hard time, he does like to hear what few anecdotes I have from lockups.

He tells me, “I will be like you in the good ways, Daddy, but not the bad ones. I won’t cheat or get sick, or go to jail, or anything like that.” My son is reassuring both of us. Even ne’er-do-wells and fuckups are heroes to their boys, and as undeserving as I am, I know I mustn’t fall further into self-hatred. He needs to see that there are parts of me that are good, parts that I want him to have.

”You have my ears,” I tell him; “you have my love for family, and my head for dates. You like sports and music and horses, just like me. You are kinder than I was, and braver, and those things make me proud.”

Tonight, on the way home from the park, we listened to the song again, and the final stanza:

I promised you, Dad, not to do the things you've done

I walk away from trouble when I can

Now please don't think I'm weak, I didn't turn the other cheek

And Papa, I sure hope you understand

Sometimes you gotta fight when you're a man.

David finds a new theme in the old tune. “Dad, I guess when I’m older there will be things you will have to learn to understand about me.”

I promise him it will be so.