Schnozzes and Stakeholders: Looking for a Truth about Bradley Cooper's Prosthetic Nose

A few years ago, as Black Lives Matter convulsed the country, my alma mater appointed a commission to discuss changing the school mascot. My beloved Carmel High had been the “Padres” since it opened in 1940. St. Junipero Serra, founder of the California missions, is buried one mile from campus. The Padre was a fitting symbol for eighty years, until, as the Great Racial Reckoning began, a great many people began to point out that the real padres treated the Native Americans rather shabbily. Perhaps, as Confederate monuments tumbled and the names of enslavers were removed from college buildings, Carmel ought to reconsider the Padre? Some folks thought so.

I originally wrote about this in 2021, while the commission was busy surveying the community. I can report that the end result was, not surprisingly, that the mascot remained. The commission found the various stakeholder groups to be evenly divided; there was no consensus on whether we should change the name, and the commission concluded that the issue should be tabled until there was a clear majority in favor of a change.

Those who wanted to change the name protested the commission’s inaction. They argued that the commission had failed to prioritize the stakeholders correctly. The commission gave equal weight to six groups: current students, faculty and staff, alumni, parents, voters living in the school district’s boundaries, and Native American groups. The activists were outraged that affluent, overwhelmingly white alumni were given the same stake in the issue as the descendants of Native Americans tormented and abused by the “padres.” The alumni snapped back that it was absurd to give any say to people who had never set foot on the Carmel High campus.

It is not easy to decide controversial questions. It is impossible to decide when we can’t even agree on who should be doing the deciding.

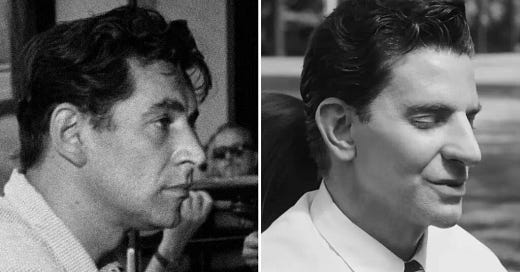

I thought of the Padre battle when I read about the current kerfuffle over Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic nose. Cooper will play the conductor Leonard Bernstein in an upcoming biopic. Cooper is not Jewish, and Bernstein was. Not all Jews have big noses, but the great conductor and composer did – and they’ve fashioned a fake one for Cooper to wear. The outrage was instant when the first stills from the production were released, and the anger has intensified with the release of the film’s trailer.

Today, the three Bernstein children released a statement defending the use of the prosthetic nose in the casting of an actor to play their beloved father. For many, that settles the issue. The Bernstein kids are the ultimate stakeholders in their papa’s story, and if they are okay with Bradley Cooper’s fake schnozz, shouldn’t we all be?

Bernstein on left; Cooper with prosthetic nose on right.

Others point out that while the Bernstein children are indeed entitled to their view, the issue is larger than one man and one family. Jews have been mocked for their noses for centuries; the enormous, hooked nose is a staple of anti-Semitic caricature from the Middle Ages to the present day. The Bernsteins can’t issue a plenary indulgence that erases anti-Jewish tropes.

Yesterday, I posted a short video on my Instagram. I moved my head side to side to show my profile – and my own large nose. My father was a Jewish war refugee. I am daddy’s spitting image, and I have a big – some would say, stereotypically Jewish – proboscis. I have been teased for it.

In my video, I said I wasn’t in the least bothered by Cooper’s prosthesis.

I didn’t think much about the Insta post, which lasted 26 seconds. Some friends pushed back after they saw it, gently reminding me that no matter how big my nose may be, I cannot speak for all Jews. “Your feelings are valid, Hugo,” a friend emailed – “But they are yours.” I took the point. We filter everything through our own unique set of identities and experiences. “I am a Jew with a great big nose, and I wasn’t offended” is a perfectly valid statement! But as my friends pointed out, others may infer that I am saying something else: If I’m not offended, then no one else should be either.

The Bernstein kids are stakeholders. In a very small way, I am a stakeholder. My great-grandmother and countless other relatives perished in the Holocaust. I have heard my share of anti-Semitic abuse. I have davened, and danced, and studied enough Torah to say, yeah, in every way that matters, I am a Jew. (One with a nose that is already big and growing larger as I age.)

Me and my nose.

Jews who see a vile anti-Semitic trope stuck on Bradley Cooper’s face? They are also stakeholders.

Who isn’t a stakeholder, though? In our terminally online culture of outrage, most of us feel invested in dramas that have damn all to do with our own circumstances. If you aren’t related to the Bernsteins, and you aren’t Jewish, and you’ve never been mocked for your nose, but you really loved West Side Story, does your opinion count? As much as mine? As much as the Bernstein kids? As much as the young woman with curls and a classic Ashkenazi nose who endures snickers and teasing in the high school hallway?

The Carmel school board spent more than $100,000 surveying the community. They paid historians to research the origin of the Padre mascot, and they paid the travel expenses for Native American activists to give testimony before the commission. In the end, the status quo prevailed because no one could agree on whose feelings should carry the greatest weight. Everyone with an opinion on the matter had a deeply felt, impassioned sense that their voice deserved to be heard. The Native Americans said, “Our voices count most.” The current students said, “Our voices count most.” The parents and alumni said, “Our voices may not count most, but we damn well matter.”

The attempt to change the mascot foundered on the question of defining stakeholders.

Defining stakeholders is perhaps the most interesting part of the Cooper/Bernstein nose question. Anyone can say, “This offends me” or “This doesn’t offend me,” and they have spoken well for themselves. Who – if anyone – has the moral stature to say, “This is offensive” and have their view prevail? Who has the gravitas and the universal credibility to shift the question from one of personal perspective to one of objective truth?

If the answer is “no one” – and I suspect it is – then there is only one solution: listen to everyone with compassion and accept that there is no hope of making everyone happy. That’s not very satisfying, but it has the virtue of being honest.