Britney Spears is having a remarkable 2021. She’s the subject of a riveting new documentary. The courts are open to reassessing the controversial conservatorship she’s been under for a third of her life. Her contemporaries (Britney’s 39, either a very young Gen Xer or a very senior Millennial) are pumping out half-a-dozen literary and journalistic reassessments of her influence a day. Britney has become a yardstick for measuring how far we’ve come as a culture in the 22 years since she became a pop icon at 17.

In the post #MeToo milieu, perhaps the central reassessment revolves around how the culture sexualized a pretty, underage teen girl – and how, wrongly, we attributed power and agency to Britney that she did not yet possess. (And of course, as the subject of a conservatorship, still does not possess, as a nearly middle-aged woman.) Herself a one-time teen superstar (at least in the world of journalism), Tavi Gevinson wrote a brilliant analysis of Britney and in New York Magazine earlier this week. The title sums up Tavi’s point: Britney Spears was Never in Control.

At the same time that young women are disadvantaged by age and gender, youth does carry currency, which can be mistaken for power. If you are a woman, however, this currency is not on your terms. When my abuser said he thought that it was I who “had all the power” while he was a hapless, insecure, wealthy, much-older-than-me man who didn’t know what he was doing, I at first believed him. I was in a splashy phase of my career. I did get us into parties. I was insecure, too, and terrified of appearing naïve, but I was also aware that my youth was an asset, no matter how uncertainly I wore it, and from that I could muster up a performance of self-assurance, and so: I was outwardly confident. But as the writer Anna Wiener put it to me, “Confidence is not a vector of power.”

Less than a month after my 17th birthday, on Father’s Day 1984, a man paid me for sex for the first time. Until that Sunday afternoon in June, I’d never touched a man sexually. Until that afternoon, I was a virgin; I’d kissed two girls, but never gotten further than “first base” with either. In the space of a little over an hour, this man became my first “everything else.”

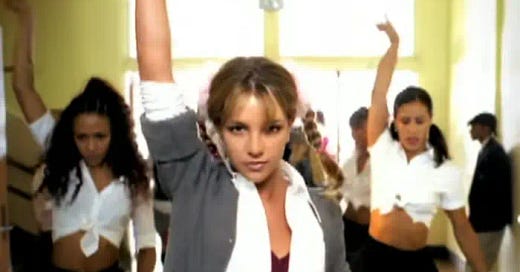

I was the same age Britney was when she made the era-defining video for “One More Time,” and became an overnight sex symbol.

Mike was a sailor in the Navy, perhaps 30. We had sex in the Casa Munras motel in downtown Monterey; when he pushed me out the door after we were finished, he pecked my lips and peeled a $20 bill off a bankroll. “Take a taxi, whatever the fuck you want,” he had said. “If I could, I’d give more, but I gotta save some, you know?”

Over the next two and a half years, until my first serious mental breakdown arrived at 19, I led a completely secret second life. First on the Monterey Peninsula, then later as a freshman and sophomore at Berkeley, I met older men for sex. They usually paid me, but I could never negotiate a fee. I didn’t have the confidence for that. By my best estimate, I had sex with perhaps 70 to 80 men between the summer of 1984 and the spring of 1987. It’s not a large number; I have friends who were or are sex workers whose number of clients is well into four digits. It is a very big number in one stunning respect: it is my staggering good fortune that in the mid-1980s, I bottomed for so many men, most without protection, and never contracted HIV or any other STD.

They were all at least 10 years older than I was, and many were at least three times my age. In the summer of 1985, when I had just turned 18, I went home with a man who told me he was 66. He would be well over 100 now.

I never told anyone. I didn’t tell my first girlfriend, even when she and I had threesomes with men we would pick up on the street. I didn’t tell my therapists, even after I was hospitalized for suicidal depression for the first time one month after I stopped doing sex work. Any connection between the sex with men for money and my own despair was incidental, I decided.

I didn’t tell my first, second, third, or fourth wives. I didn’t tell the Internet when I became known as a confessional writer. Indeed, a lot of my penchant for public confession was born of my desire to conceal being a sex worker. I wrote and spoke so often about other aspects of my sexuality, and I did so with such apparent candor, that I could pull attention away from what I wanted to remain hidden.

If you’ve got five big secrets, the relief from telling four of them can help you trick even yourself into thinking you’ve come completely clean.

I did not have sex for the money. I did not have sex because I was attracted to every man I slept with. A few times, I really did enjoy what happened, but more often, it was either painful or boring. Alone in my own bed, I’d masturbate to a carefully edited highlight reel of these encounters, enjoying in retrospect what I had merely endured in reality. It wasn’t money, though that was a welcome bonus, and it wasn’t pleasure, though there were glimpses of that --- what I loved, with every corpuscle of my being, was being wanted so badly.

Being wanted made me feel powerful in a way that I had never felt before. There is no drug I’ve ever taken, no experience I’ve ever had, that comes close to the high of seeing desire in someone else’s eyes. It never lost its allure, even after I left sex work behind when my brain began to burn too hot. (I wrote more about that craving, and what it cost me, here.)

In my 40s, I started having affairs with my students again after years of being “good.” The young women were all legal adults, but in some instances, barely so. Because at that time, I never even allowed myself to think of my past doing sex work, I didn’t realize that I was partly reenacting my late adolescence, with the positions reversed. I never paid a student with money or grades, as that would have ruined the fantasy that they craved me for me. I was meticulous about securing enthusiastic consent, and I trusted that despite the age and power differential, these young women had the agency to decide what they wanted.

(I’ve written about much of this before, and I apologize if any of this is repetitive or tedious for regular readers. I am still struggling to understand my own strange and reckless life, and how that decision to go back to a motel room with a man when I was 17 became the first in a series of secret, shame-soaked choices that led inexorably to the Catastrophe that ended a marriage and a career.)

Tavi Gevinson’s piece on Britney is full of Tavi’s own story of oversold adolescent agency. “Confidence is not a vector of power,” Tavi writes. Yet when I was 17, I didn’t just feel a strange and wonderful confidence as a result of being craved by older men. I felt powerful, even when I was so tongue-tied I couldn’t set proper boundaries with clients or set a reasonable price. Their wanting me was the most powerful thing I’d ever felt, and I would take any risk and tell any lie to keep feeling it. You’d be right to say that that feeling wasn’t real power. The rush of well-being that comes after the first line of coke, or the swagger that comes after the second shot of vodka – those are fleeting facsimiles of power, and it is precisely those who feel the least agency in their sober lives who quickly become dependent on agency’s chemical, chimerical approximations.

Decades later, when I became the older man sleeping with much younger people, I felt powerless. I was a tenured professor, not an underage boy, and I had swapped one illusion for another. At 17, I exulted in being able to make older men writhe and gasp; at 17, the hunger in their eyes was rocket fuel for my self-esteem. At 17, I felt I could stop any time I liked. At 45, I felt myself in the grip of an addiction beyond my control. At 45, I knew my longing to be wanted by these young women would destroy my life, but I felt powerless to resist it.

Feelings are not facts, as they tell us in the rooms of AA. Teens who find themselves the objects of desire may feel very powerful indeed, but as Tavi points out, that power is largely illusory. Indeed, there’s an entire culture built around overselling young people’s agency, and it tends to benefit those who want to pretend that they aren’t taking advantage of the vulnerable. To the modern mind, not only was Britney Spears lied to, she was and is a world-famous symbol of the Great Lie. Just as she has paid a devastating price for that lie in adulthood, so too did the many young women (and a few young men) who were told that adolescent Britney represented authentic power.

At 17, I was lying to myself, wanting to believe I had a power I didn’t. At 45, I was still lying, this time convincing myself I was helpless in the face of a 20-year-old’s starry-eyed crush on her professor. As a boy, I confused the currency of desirability with genuine power; as an adult, I confused my own self-destructive recklessness with powerlessness.

Two bookends:

ONE: I was a freshman at Berkeley, 18 years old, when a 50-ish man in a Brooks Brothers blazer took me to his apartment in the Oakland Hills. The place was elegant, only a few blocks from where my aunt lived on Broadway Terrace. He had pictures of his children in silver frames, and books on finance and investing lined his shelves, and he had copies of Town and Country and Architectural Digest on his glass coffee table. He was the handsomest client I’d ever had, and I was nervous. Unlike any man I’d ever been with, he had the trappings of “Our Kind of People.”

He was only a little older than my father.

The handsome WASP ejaculated as soon as I touched his penis, and he laughed apologetically. “Sorry,” he said, “You’re just so hot, I couldn’t hold it.”

For weeks after, his words echoed in my brain. No praise had ever been this high. I had made this man’s knees buckle. I had never felt more like a beautiful prince. I had never been more keenly aware that I had a kind of power, even if it only seemed to work on a few.

TWO: In the fall of 2012, I had my final affair with a student. I would get to campus early, at 7:00AM, and Hayley (not her name) would meet me in my office. One morning, after we had finished having sex, Hayley had a question. “Am I worth risking your job?”

“Are you planning on turning me in?” I asked.

Hayley shook her head. “Never. I just want to know, am I worth everything you might lose?”

“I would throw it all away for you,” I replied.

Hayley beamed.

I wasn’t in love with Hayley, nor she with me. But I wasn’t lying, either. I knew she wanted to know I couldn’t resist her, and I needed to convince myself that I was in the grip of something greater than my own will.

All my life, I have misunderstood my own power and the power of others over me, and the cost has been immense.

Thank you, Britney, for helping clarify when I was in control, and when I wasn’t.