Sex Strikes, Abortion Laws, and the Real Meaning of Lysistrata

My next two posts after this one will be for subscribers only! If you like this one, and don’t want to miss what’s coming, please do consider a paid subscription. It keeps the lights on too! Thank you!

Oh, what to do about Texas?

If there’s one evergreen on the left, it’s the half-serious invocation of the “Lysistrata option.”

Most people who have heard of Lysistrata have not, in fact, read the Aristophanes comedy. That’s fine; your friendly neighborhood grocery store bagger is not in the business of shaming people for not having had the opportunity to read the classics. The problem, of course, is that most people who have heard of Lysistrata only get one aspect of the story.

“It’s when a bunch of women in ancient Greek times got together and pledged to stop having sex with men until the guys stopped a war? Right?”

Well, yes, but there’s a key element to the story that’s left out of that summary – and that has direct relevance to how we think about creating sustained resistance to the rising tide of anti-abortion legislation.

Lysistrata is set in the Peloponnesian War, which as you might remember (my students should!) was between Athens and Sparta. I don’t want to push this analogy too far, but Athens and Sparta were the Red and Blue states of their time. They had vastly different understandings of how to order the common life, of what it meant to be good, and of what it meant to be Greek. At different times in their histories, they mocked each other, deliberately misunderstood each other, reluctantly cooperated with each other, and, in the end, fought each other in a prolonged and bloody civil war.

Ring any bells?

I will not foist upon you the Cliffs Notes summary of the play, but here’s the key point everyone misses. It is true that in hilarious but effective fashion, an Athenian woman named Lysistrata gets women to commit to withholding sex (sex they themselves very much want) until the lads agree to stop the war. What is also true is that Lysistrata knows that none of this will work unless she gets the Spartan women to join her. It is Lysistrata’s alliance with a Spartan woman named Lampito that proves pivotal – at the first rally before the sex strike, most of the women are unwilling to agree to Lysistrata’s plan, until they see that the Spartan women will support it as well. The plan only works because the Athenian women are willing to put aside their snobbery and contempt for Spartans, and work in unity with those whom they think of as barbaric, rough-hewn hillbillies.

(Whenever Lysistrata is produced on stage today, Lampito’s character always speaks a rural dialect of the sort lampooned by urban elites. When the play was done in 18th century England, Lampito spoke as a Highland Scot; when it was done in mid-20th century America, her accent was generally performed as Appalachian. Whatever accent signifies coarseness and ignorance to an affluent, smug, urban audience will work.)

The problem, of course, is that the would-be Lysistratas of our age have done an outstanding job in recent years of cutting off the Lampitos to whom they were once connected by blood or affection or memories of drill team in high school. The Trump Era brought us the Great Unfriending, with the constant reminders that it was not only okay, but even virtuous to deny one’s warmth and one’s Facebook page to those who supported the Orange Man, or who today are reluctant to get vaccinated. Even in Texas, the divide between urban liberals in places like Austin and rural and exurban conservatives in the rest of the huge state is so vast that they have little occasion to speak to each other, much less cooperate.

Men and women increasingly don’t date across ideological lines – and I suspect, though it’s harder to prove, that more and more women aren’t sustaining friendships with other women across those same divides. The pandemic has accelerated a Great Re-Sorting not only online, but in real geographic terms. Right-leaning Californians are moving to Florida and Texas; progressives in those states are at least making mutterings about moving to more congenial climes, particularly as redistricting and voting restrictions seem likely to entrench Republican majorities.

Bottom line: in 2021, our latter-day Lysistratas can’t bring themselves to talk to Lampitos. Miranda, the activist and journalist in Montrose (a hip Houston neighborhood) has already unfriended Everleigh, her best friend in fourth grade when they were growing up in small-town Sour Lake up in Hardin County. Everleigh doesn’t believe in vaccines; Everleigh voted for Trump. Miranda decided a long time ago that happy childhood memories weren’t worth tolerating the scandal of provincialism and deplorable ignorance. She blocked Everleigh in January, after the insurrection. Miranda knows she can’t reach out now; it would be both embarrassing and useless. They inhabit different worlds.

Miranda won’t take the risk that Lysistrata would.

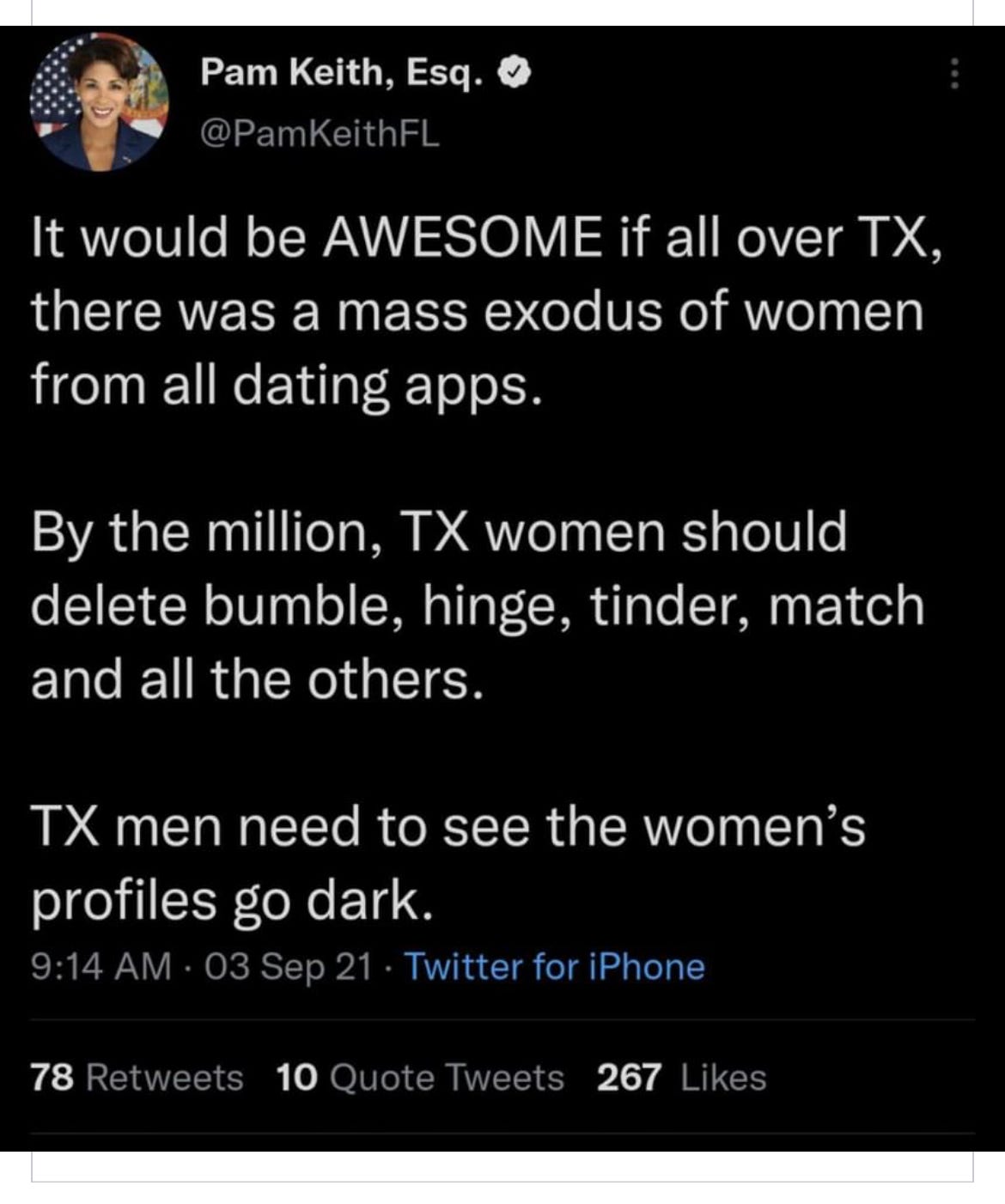

The sex strike in the Aristophanes play works because it happens on both sides. I assume that most folks calling for a sex strike in Texas are joking, but their humor is born of genuine frustration and fear. Something must be done at once for the women of Texas, and maybe cutting men off will be a catalyst to dramatic action. Of course, if this is unilateral – as it will be, because no one believes in building alliances across ideological lines anymore – the only “cut-off” men will be the progressive urban ones. Do we imagine that Alastair, who writes code for an Austin start-up and has had some recent success with the ladies on Hinge, will be so motivated by his sudden and unpleasant state of politically-motivated chastity to somehow influence Timmy in Tyler to change his views?

That’s now how this works.

There’s another reason the Lysistrata option will fail. I’ve been many places, because I’m a curious sort, and I’ve hung out with a lot of pro-lifers in my day, while remaining pro-choice down to my corpuscles. Here’s the thing: the strongest and most motivated activists on both sides of the abortion issue are, of course, women. The pro-life movement has historically had women as both its most active footsoldiers and its senior leadership. Spend enough time with women on both sides, and you’ll hear endless laments of mutual incomprehension. My pro-life female friends say things like, “I get that you support abortion because you’re a man. What I’ll never understand is how a woman can make war against her own innocent child.” My pro-choice female friends say, “I’ll never come to terms with how many women can be so complicit in their own oppression.”

If this were a Greek play, each group of women would turn to the audience while pointing at their ideological rivals and recite in unison, The gods gave them eyes! How can they not see?

I think the new Texas law is horrid. I think it is wrong both in its goals and in its methods, and I remain hopeful that the courts will come to strike it down after we have evidence of its misuse. In the meantime, instead of just posting memes for one’s ideologically compatible friends and preaching yet another impassioned sermon to a captive choir, let’s revive the real story of Lysistrata. The Aristophanes play portrays women quite positively: strong, decisive, sexually exuberant and politically savvy. They are also willing to build ideological bridges to erstwhile enemies, and willing to surrender their mutual contempt and anger in order to pursue the common good.

If you want to change this country, that’s as good a place as any for all of us – regardless of sex – to start.

————

Students in my Women’s History class will remember that organized American feminism was born primarily out of the Temperance Movement. Loretta Lynn’s country classic is always worth a revisit. I played it a dozen times while writing this newsletter.