The Noom Diet is Probably NOT the Hero's Journey

This is a public post, and I thank you for reading (and perhaps, sharing) it. If you’d like the full experience, with additional subscriber-only posts, please explore some options by clicking the button below!

I give away the satisfactions of food and take

desire for food: I’ll be travelling light

to the heaven of revisions.

Since April 5, I’ve been following the Noom diet. I’ve gone from 226 pounds on Easter Sunday to 192 as of this morning. My goal is 185, which is what I weighed during the last few years of my teaching career.

The Noom program, which you have probably seen or heard advertised, works via an app on your smart phone. It asks you to enter your daily food intake; it tracks your steps and your exercise; it provides coaching and psychological reinforcement. You are welcome to email me if you have more questions, but I do not write today in order to sell you on anything.

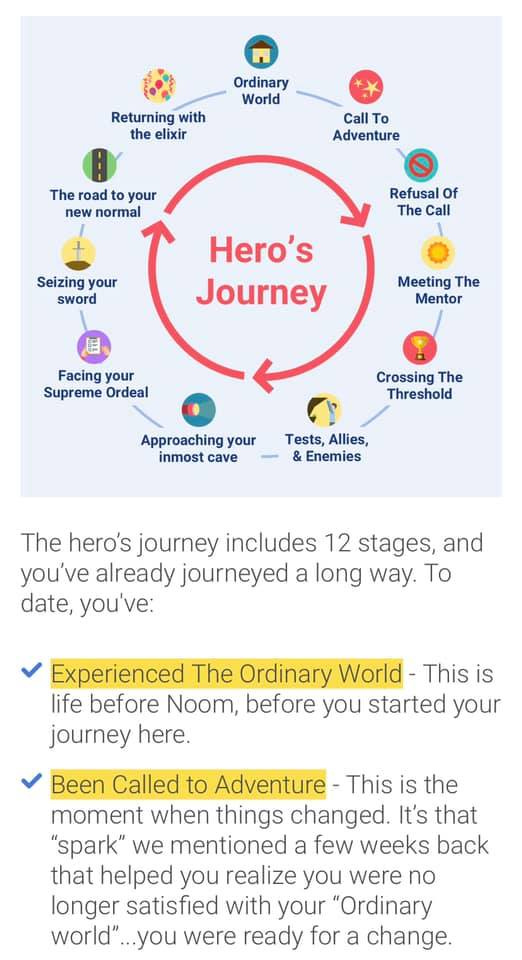

A week or two ago, this screen launched my daily “tune-up” on the app.

For most of us outside of folklorists and disciples of Carl Jung, the idea of “Hero’s Journey” entered our cultural consciousness in 1988, when Bill Moyers broadcast his famous interview with Joseph Campbell. In that interview, available here, Campbell explains that “Everyone is a hero in his birth. He has undergone a tremendous transformation from a little, you might say, water creature. living in a realm of the amniotic fluid and so forth, then coming out, becoming an air-breathing mammal that ultimately will be self-standing and so forth, is an enormous transformation and it is a heroic act.”

Our heroism at the moment of our own births sets the template for our lives.

The Hero’s Journey is the template for most folk tales, and for most movies. Every screenwriter I know is at least passingly familiar with the stages that Campbell described and that Noom reproduces in the image above. When you enjoy a movie, Campbell devotees say, part of that pleasure is in recognizing the familiar progress of the hero; when you feel alienated or uninspired by a film, it is because its creators failed to adhere to the rules of the journey.

If being born is part of the hero’s journey, then of course, so is everything else — going on a diet to lose 35 pounds very much included.

I don’t like that framing, even as I recognize that my own resistance to it is, as the kids say these days, problematic. Call it the WASP ideal of service, the Protestant work ethic, or Jewish guilt, but it strikes me that in order to be genuinely heroic, the hero’s journey must be rooted in something beyond himself or herself. In many of the classical versions of the story, the hero starts out self-absorbed, and as the result of his journey, becomes devoted to others, even (often) at great cost to his own safety. A diet — particularly one that requires daily reflections, calorie monitoring, and weigh-ins — calls the dieter inward. For those of us already prone to being unduly captivated by our own stories, a focus on body transformation may result in a change in how we look to the rest of the world, but it’s not at all clear that we’re providing any tangible benefit to others.

It is true that my loved ones are pleased by my weight loss. “You look more like your old self,” remarked my mother. “I’m glad you’re going to be healthier,” my daughter said; “You have to live a long time.” To the extent that my improved appearance and health reassures the family, then the effort is a form of service.

I’d be dishonest, of course, if I claimed that vanity wasn’t a significant motivation as well.

Nearly 30 years ago, after the end of my first marriage, I plunged into a brief but intense period of seriously disordered eating. At one point, around the time Bill Clinton was elected president, my weight fell to 148 pounds. A rumor went around the UCLA history department that I had AIDS. I was unattractively gaunt, but I saw my body as nearing a perfection it had hitherto never achieved. I had a serious case of dysmorphia, rooted in self-hatred. Watching my flesh fall off was a variation on my old penchant for self-mutilation.

Escaping that particularly brutal eating disorder was the hero’s journey. Not only was it enormously psychologically difficult to put some weight back on, the real battle was to stop the self-loathing that left me so preoccupied with Hugo that I had barely any regard for those around me. It was my second wife, Sara, who pushed me to gain weight as soon as we started dating. She promised she’d find me sexier if I did, but she also urged me to be less focused on how I looked — and more on how my body could bring pleasure and comfort to others. It was a brief and unhappy marriage, but I am grateful she helped extricate me from that desperate self-absorption.

The politics of weight loss, fat acceptance, and beauty are beyond the scope of this post. (I taught a course on that subject for years). I will say simply that while I would hate to negate anyone else’s experience, or to discount what is helpful to others, I have no time for the omnipresent misapplication of the notion of the heroic. I’m glad I have dropped a few pounds, I am modestly proud of my efforts, and I find it borderline offensive to describe this transformation as akin to Ulysses returning to Ithaca.

With apologies to the Beach Boys, the Doors, the Eagles, Jackson Browne and all the other luminaries of the angel town, Los Lobos is indisputably the greatest Los Angeles band. They just released the bluesy new single, “Misery” from their upcoming album, and it’s very fine. The video below it is from the band’s 1987 album, “By the Light of the Moon,” which would easily be one of my Desert Island Discs.