The Whirligig of Time: What the Quiz Show Scandals Can Teach Us about Surviving Cancel Culture

If you or someone you know has also been cancelled please let me know if there is a cancel club reunion because I could use some time off my couch!

-- Chrissy Teigen on Instagram, July 14, 2021

Ms. Teigen has been cancelled. Lots of famous, microfamous, and utterly unknown people are cancelled these days. To be fair, there have always been cancellations; decades ago, people lost their jobs for having extramarital affairs, or for being Communists, or for speaking up against whatever injustice irked them. It was just that the humiliation was so much less public back then, or so we are led to believe.

When I think about what advice I’d give Chrissy, as a fellow cancelled person, I think about a man who was cancelled more than 60 years ago – and who lived for decades with a name associated with scandal and disgrace.

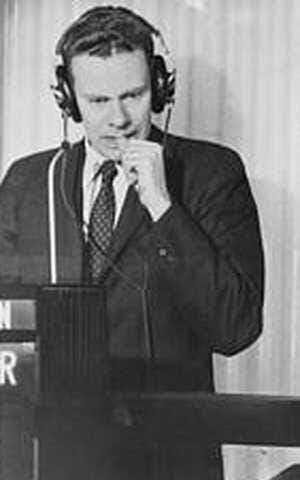

If anyone could say he was a charter member of the cancel club, it would be Charles Van Doren, the scion of a prominent academic family who in 1956 became an instant national celebrity – and soon thereafter, became a convicted perjurer and the face of the “quiz show scandals” that rocked television in its infancy. For all his charm, education, breeding and acumen, Van Doren chose to be a fraud – allowing himself to be fed the answers by NBC in order to become the handsome, telegenic star of “Twenty-One,” briefly the most popular game show of its era. The revelations that Van Doren had cheated, and his subsequent testimony before grand juries and even Congress, shattered his reputation and humiliated his entire family.

If you’re under 65, you probably only know the name Charles Van Doren because of Quiz Show, the critically acclaimed 1994 Robert Redford film, with Ralph Fiennes as Charles and the great Paul Scofield as his father, the celebrated Columbia professor Mark Van Doren. (If you haven’t seen it, stream it on Amazon Prime or some other platform; it holds up well.)

The film was made without Charles Van Doren’s participation, but not against his wishes. As Van Doren recounted in a 2008 New Yorker article, Redford badly wanted Van Doren as a consultant – but the latter refused, holding true to a promise never to profit from his dishonesty. Only in that one New Yorker article – which Van Doren penned at age 82 – would he tell his side of the story. He died in 2019, age 93.

When Van Doren’s scandal broke, he lost his job as a pundit at NBC. Van Doren had had no training as a journalist, but he was so telegenic and well-liked, the network had found a way to keep him on camera even after they had rigged his defeat on Twenty-One. Van Doren had followed his father into a teaching position at Columbia; following his perjury conviction, the university asked him to resign. (I was no Charles Van Doren; a gig writing for the Atlantic is not a broadcast position at NBC, and Pasadena City College is not Columbia. Still I know damn well what it is like to lose multiple sinecures – in academia and journalism -- simultaneously.)

When his world crumbled, Van Doren didn’t complain, or lament, or blame anyone other than himself. He took full responsibility before a House Committee investigating the scandals – and then, did his best to disappear. Unlike almost any of us today, Van Doren accepted the irrevocable finality of cancellation. Reading between the lines of that single New Yorker essay, Van Doren’s breeding becomes clear: for a certain kind of gentleman, no temptation is more foul than self-pity. Van Doren was clearly manipulated by NBC, as all the contestants were, but he blamed only himself – and having given one single confession, he kept silent for decades.

Van Doren did not quite disappear. He served as an editor at Encyclopedia Britannica; he worked as a ghostwriter and an editor, and – despite what the film claims in its epilogue – did find a way to return to teaching eventually, though not in the Ivy League. He was devoted to his wife and children, his friends and colleagues. He also resisted the urge to explain himself. From that New Yorker piece:

I can sit with my thoughts without having to respond to people who say, “Aren’t you Charles Van Doren?” Well, that’s my name, I say to myself, but I’m not who you think I am—or, at least, I don’t want to be.

I am not who you think I am – but I don’t have to prove it to you. That is, perhaps, Van Doren’s greatest lesson for me, for Chrissy Teigen, for the growing army of the disgraced and the cancelled. Over and over again, Van Doren had what I can only dream of: the chance to make good money telling his version of the story. Every cancelled person imagines that if they could only find the right words on the right platform, they could get through to everyone who despises them, and they could set things right. Van Doren knew that was hubris: reading his words, I can hear him saying, “I am not who you think I am, but I don’t need to change your mind about that. I can be the butt of your joke or your morality tale for six decades and still, still, I will not be drawn into defending my life.”

Unlike me, but very much like Chrissy Teigen, Van Doren did not need to worry about how to make a living. His family wealth had not vanished as mine largely has. To paraphrase Forster, Van Doren stood upon money as upon an island, and that firm foundation beneath his feet allowed him to avoid what so many of the cancelled experience – a terrifying and bewildering plunge into insecurity and even homelessness. At times, I am tempted to discount Van Doren’s calm acceptance of his fate for that reason alone. But as Chrissy Teigen’s abject pain reminds us, when it comes to the psychological impact of public disgrace, even great wealth does not offer much protection from the storm.

Van Doren writes:

A small gift from my father helped me through. He had wrapped a square box in tissue paper, sealed with Scotch tape. The box contained a gyroscopic compass, the kind you can start spinning and put on the edge of a glass, where it will stay upright till the spinning stops. A card in the box read, “May this be for you the whirligig of time that brings in his revenges.” I knew the quotation. It’s from “Twelfth Night.” Feste, the mean-spirited clown, has been unmasked, but those are his last words, thrown over his shoulder. The play’s audience knows that somehow he will survive and live to taunt some other master. I didn’t ask my father what he had meant by it, because I knew he was saying that I, too, would survive and somehow find a way back.

Van Doren never quite made his way back – but he did make his way forward. He made that way forward with restraint, with gentleness, and with a willingness to devote his considerable literary talents not to restoring his own tarnished legacy but to making other people’s work much, much better.

When I am at my most anguished at all that I lost, and at my most crushed by all the contempt that is still – still – thrown my way, I try as hard as I can to remember Charles Van Doren, and the dignified, courageous, and profoundly honorable way he lived with his lifelong notoriety.

If we ever build a clubhouse for the cancelled, we shall hang portraits of our heroes and inspirations on the wall – and Charles Van Doren’s picture must enjoy pride of place.

I’m not sure it has much to do with this newsletter, but I wrote this listening to one old favorite on repeat: Tom Russell’s Gallo Del Cielo. It’s been covered many times, and it’s an Americana classic and a comfort. It makes me cry as often as not.