“It’s 3:30,” David complained. “They haven’t kicked off yet.”

I noted that it was so. The Super Bowl was running late, and my son was unhappy. I asked him to consider his peers in the Eastern Time Zone, some of whom would be sent to bed before the conclusion of the game, and consider himself lucky to be a Californian. David grumbled, but accepted the truth of his good fortune.

The kickoff (which finally came at 3:41PST, eleven minutes late) was delayed for who knows how many small reasons, but one overarching big one: we ask much too much of the Super Bowl. Because it is the last collective American experience shared in real time, a football game must serve as an opportunity to mourn various recent tragedies, pay tribute to heroes fallen and living, and sing an ever-longer list of hymns to a fractured nation. Where once we just had the Star-Spangled Banner, now the anthem is preceded by “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” as well as “America the Beautiful.” So many paeans! So much heartache and hurt and anguish and discontent that must be addressed in one jam-packed pre-game show.

The Super Bowl broadcast is like a rococo church. Just as 18th-century decorators covered every inch of sacred space with gilded doves and cheery cherubs, the Super Bowl production squad crams every moment of airtime with spectacle and symbol. So many who need to be honored, recognized, feted, remembered, acclaimed, thanked! So little time! Under the circumstances, it was a miracle that the ball was put in play only 660 seconds behind schedule.

Our national pastime, of course, is not football. (Or baseball, for that matter.) Our national pastime involves reenlisting, day after day, as footsoldiers in the culture wars. We are animated by the sense that millions of our fellow Americans are deluded at best, or enthralled by the demonic at worst. So when we watch the one event that captivates both the Saved and the Damned, the Woke and the Slumbering, the Decent and the Depraved? Well, we look very hard to see which side — ours or theirs — is ascendant on the screen.

Culture warriors debated which team was more MAGA. (Kansas City has Kamala-endorsing Taylor Swift as the world’s most famous football fan — but also has anti-feminist and traditionalist Catholic Harrison Butker handling kicking duties. Does one cancel out the other?) Despite the claims of conspiracy theorists, though, you cannot easily script the outcome of the game on the field. Which team wins, and how they win, is almost impossible to politicize. Each team has plenty of fans on both sides of our ever-expanding ideological gulf.

It falls to the halftime show, and not the teams, to illustrate (and not just illustrate, but widen) the stark reality of the cultural divide. For decades now, the halftime show has been the most watched musical performance of the year — ten or twelve minutes of diversion, celebration, and provocation. The American right, high on the staggeringly rapid advances of the newly-installed Trump administration, longs to reclaim the NFL as a bastion of conservative and patriotic values. A dismayed and disarrayed left, trying to find its footing, longs to reassert its hegemony over this singular pop culture event. For one more Sunday afternoon, they evidently did so.

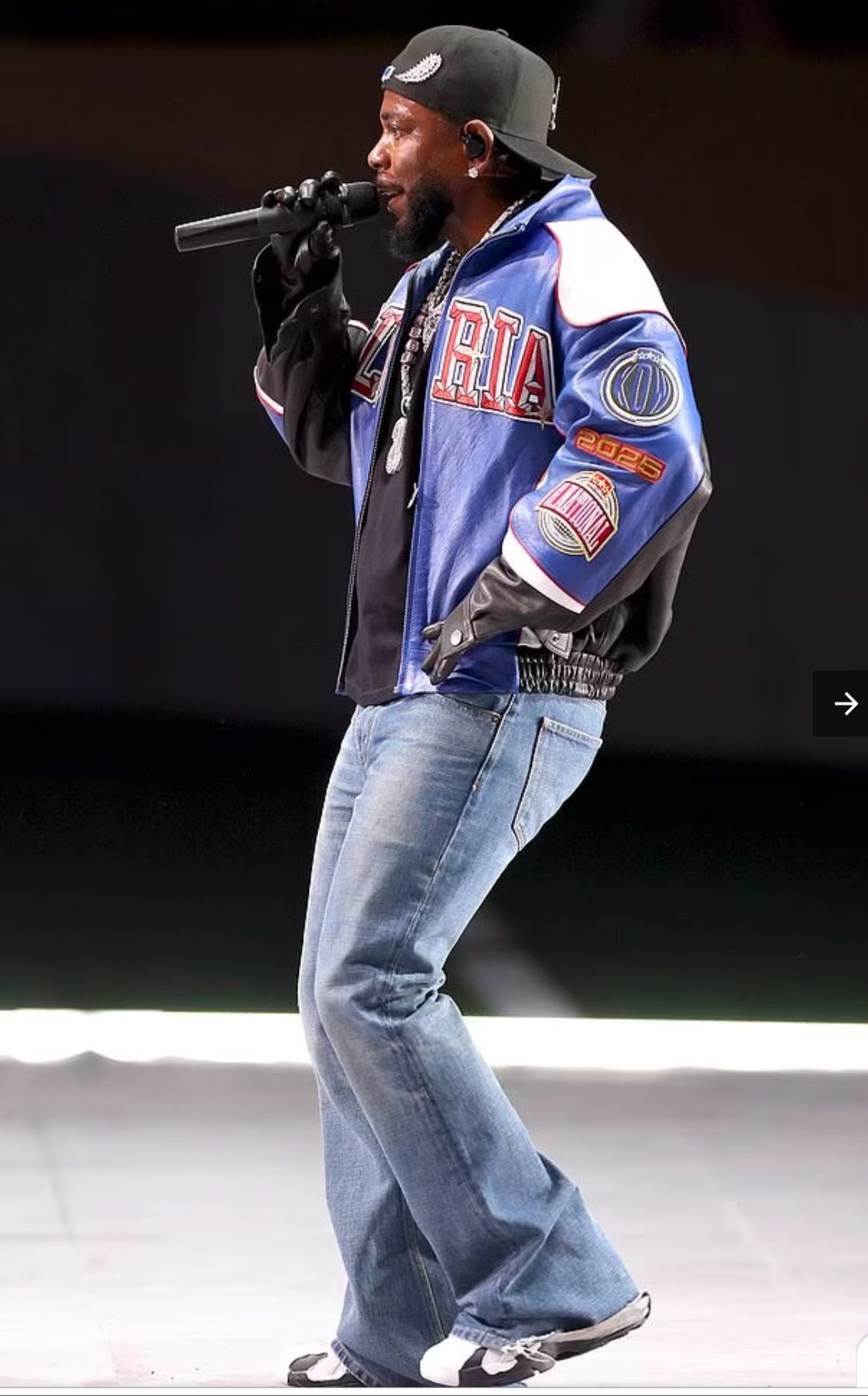

Kendrick Lamar and some excellent jeans

Each side knows the other is watching. Each side knows that they will judge the success of the halftime show by one standard: the anger it provokes in the enemy. And sure enough, as soon as Kendrick Lamar’s set was done, many of my righty friends took to social media to decry his performance as boring or hateful or both. My lefty friends took screenshots of all the conservative complaints, posting them with derisive glee.

A widely shared meme. Look at all them mediocre white men, amirite?

To the truly partisan mind, the success of any artistic project is judged by one rubric above all others: the outrage it arouses on the other side. When you’re reeling and dispirited and scared, as the left is these days, there is both relief and pleasure in discovering that you still possesses the power to provoke and dismay the ascendant right.

Kendrick finished his performance with “Not Like Us,” the infectious Grammy-winner for record of the year. As anyone under 40 knows, “Not Like Us” is a “diss track” — the winning salvo in Lamar’s long-running musical feud with fellow rapper and rival Drake. (“Diss” is, I think, short for “disrespect.”) “Not Like Us” calls out Drake as a pedophile, a claim over which Drake has filed a defamation suit. Of course, it’s not only got a very catchy beat, the song perfectly captures the rigid moral binary of the American moment. Each side is very clear that the other is “not like us.” We are compassionate, while they are cruel. We are rational, while they are enslaved to superstition. We see clearly, while they are willfully blind. There is no talking to these wretches, and no hope of compromise. Only the defiant, sneering declaration that the divide is permanent and enduring.

“Not Like Us” elevates a personal diss into a celebration of national divorce.

Kendrick is lionized not merely for his incandescent talent, but because he got into an increasingly nasty public feud with a peer — and won spectacularly. For an anxious and angry people, Kendrick Lamar’s victory over Drake is a proxy for all the imagined victories to come over the impure, the vile, the bigoted, and the mediocre. For the duration of halftime, a bruised and battered left got to feel as if it were 2020 all over again. Here was a proud Black prophet, a Pulitzer Prize winning writer, dissing not just an inferior competitor but indicting an entire nation. How cathartic to hear and see him. How satisfying to see the right-wing, as it always does, reflexively take the bait. The great flood of think-pieces began to appear before the game was over. It will be Wednesday at the earliest before the deluge dries.

I watched the halftime show with David and his mother. When it was done, my ex-wife uttered a soft and enthusiastic “wow,” and then asked what I thought.

My son answered before I could: “You already know, mom. Dad is going to say it was ‘superb.’” His mother laughed. I feigned mock hurt at being so predictable.

“No, I was going to say it was ‘sublime.’”

More laughter from my loved ones. It is true that I have praised every halftime show for forty-five years, and usually pronounce this year’s version to be the best ever. I am conscious of what I am saying and why I am saying it, and I am never lying as I offer effusive approval. I gently reminded my son that to be easily delighted (which I am) is not a vice. To be nearly impossible to offend is, more importantly, a profoundly undervalued virtue. It is also an especially unpopular virtue at the moment, but it is one I commend to my children and my readers. The capacity to defuse provocations — to break the dull and damnable “diss cycle” — is a talent we desperately need to develop.

They — whoever they are — are just like us. To say otherwise is to fall prey to an illusion that functions to distract, to dismay, and to destroy.

Defy the dividers.

I do not charge for subscriptions any longer, and my writing is free to all, but if you are interested in supporting me and my work, I would very much welcome the one-time or occasional cup of coffee. You can buy me one here. Thank you!

I've always been a cheap date. And I've pretty much always been happy. There is certainly a connection between being easy to please and hard to offend, and contentment.