Three Dog Night and Dixie: the Innocent, Complicit Pluralism of my Childhood Music Class

In these divided and angry days, I am thinking of Mr. Purdy’s music class at Carmel River School.

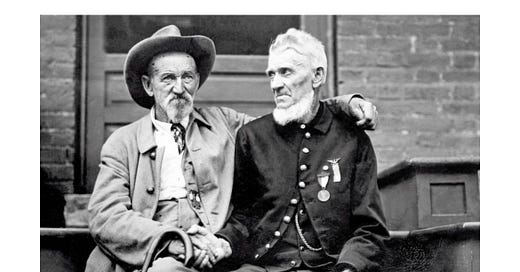

Several generations of children passed through Bill Purdy’s music education courses in the Carmel Unified School District. A tall, angular man with a huge nose and a larger smile, Mr. Purdy taught the sullen, the tone-deaf, the over-enthusiastic and the generally bewildered to sing. He was a full-time public elementary school music teacher, an alien concept to anyone born after about 1980.

I was at River School from 1974-78, from 2nd grade through 5th, and at least twice a week throughout those years, my classes trouped to the music room to learn songs and hear stories from Mr. Purdy.

Mr. Purdy kept an ear on pop radio. In 4th grade, we learned “Joy to the World” by Three Dog Night, and sang it at a school show for our parents. Even my grandmother was delighted, and because it was the indulgent and civilized 1970s, no one batted an eye when their sweet 9-year-olds belted out lyrics like these:

Jeremiah was a bullfrog

Was a good friend of mine

I never understood a single word he said

But I helped him a-drink his wine

And he always had some mighty fine wine

Singin' joy to the world

All the boys and girls now

Joy to the fishes in the deep blue sea

Joy to you and me

And if I were the king of the world

Tell you what I'd do

I'd throw away the cars and the bars and the wars

And make sweet love to you

You know I love the ladies

Love to have my fun

I'm a high life flyer and a rainbow rider

A straight shootin' son-of-a-gun

I said a straight shootin' son-of-a-gun

Good stuff.

Mr. Purdy was, in the words of one of his fellow teachers, “as gay as a bunny.” He was the first adult man I knew who was gay – and though it was never discussed except in hushed jokes and whispers – he did a great deal to spread acceptance in our conservative small town. And to be who he was and to teach us a song with lyrics like these? Mr. Purdy had courage.

He also loved history, and in 5th grade, we made our way through the American songbook. We sang a lot of Stephen Foster (when I watch the Derby, I don’t need to see the lyrics to sing “My Old Kentucky Home”). We sang what we were then told were called Negro Spirituals (“My Lord, what a Morning” was my favorite); we learned all the service academy hymns. (I have a preference for the Army’s.)

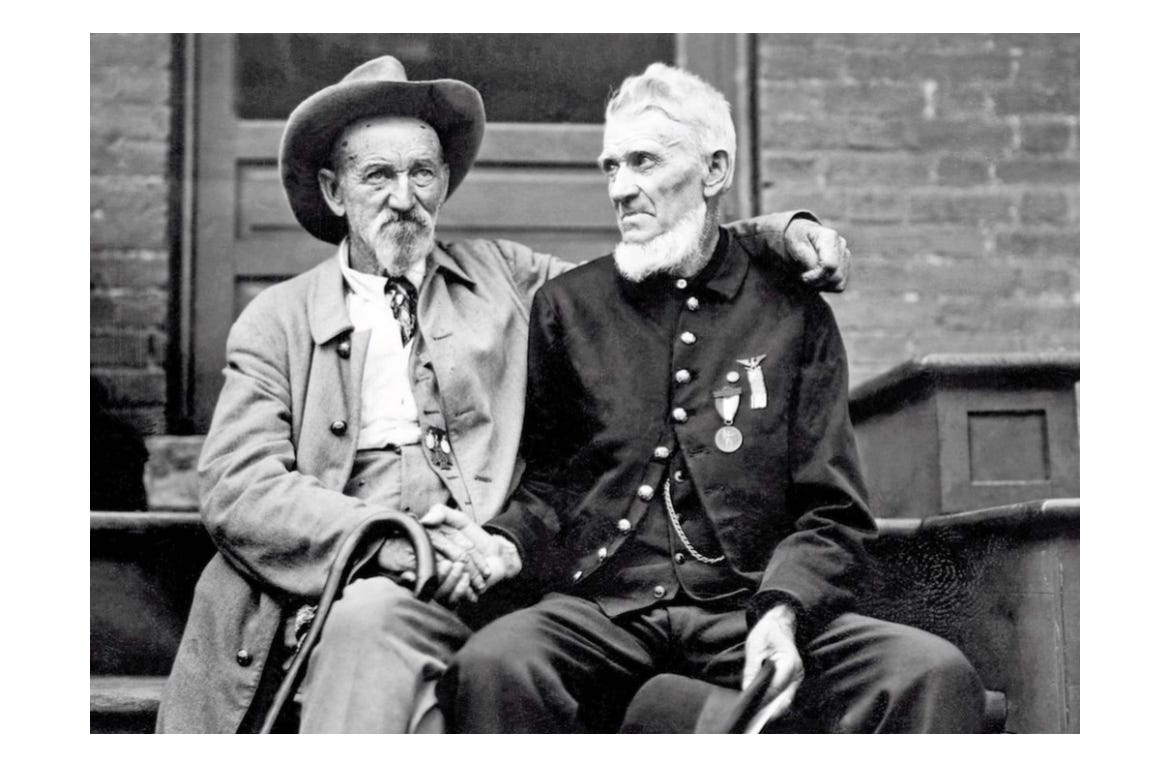

When it came time to learn the songs of the Civil War, Mr. Purdy thought it best to give us one battle song from each camp.

From the Union side, we sang “Battle Cry of Freedom” with its stirring call to end slavery:

The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Down with the shackle, up with the star;

While we rally round the flag, boys, rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

We also sang “Dixie to Arms,” the Confederate battle version of the better-known Dixie:

Southrons, hear ye Country call ye! Up! Lest worse than death befall you!

To arms! To arms! To arms! In Dixie! Lo! All the beacon fires are lighted,

Let all hearts be now united!

To arms! To arms! To arms! In Dixie!

We were elementary school children, almost entirely white, trying to do equal honor to what Mr. Purdy taught us were two equally valiant armies locked in a desperate, tragic struggle.

If I close my eyes, I can see him at the piano in the music room, mouthing the words to us as we sang to him. I loved both these songs. As I sang, I thought of brave teen boys marching to certain death, the lyrics I was singing now the last words on their lips. Even as a child, I wept to sing these songs, getting teased for my tears, desperately empathetic to all the men who fought so hard. I thought of their short lives and bloody deaths and heartsick parents.

I thought of individual courage, individual terror, individual glory, individual tragedy. As Mr. Purdy may or may not have intended, we made no moral distinction between the two sides. His sheet music came in a folder with both the Confederate and American flags emblazoned upon it; this was a war where brother fought brother, and to declare one side virtuous and the other damnable would be to miss the point of universal heroism and heartbreak.

I wonder when the last time was that a group of public school children in California sang “Dixie to Arms.” I doubt very much they ever will again.

“Both-sidesism” is mocked and derided, perhaps rightly. I come by it honestly, though, and it has proven difficult to release in my old age. I can still remember Mr. Purdy saying, “Once you’ve sung someone’s song, you can’t help but love them.”

Joy to the world, he sang; joy to all the boys and girls. And when you have music and joy and compassion for everyone, what use is there for politics and distinctions? What purpose is there to judgment and discernment when all who sing are worthy of love?

It was a privileged worldview, a naïve worldview, and to the truly modern woke mind, it was outright complicity with white supremacy. I can acknowledge all that, and still wish my children had a Mr. Purdy – even if I, who have sung the bunnies many a folk song, can’t quite bring myself to teach them “Dixie to Arms.”