We Can Never "Set the Record Straight:" The Illusions of History and Memoir

“I don’t know if I have a memoir in me,” a friend mused to me last week, “But I sure would like to set the record straight.”

It’s an interesting phrase, “set the record straight.” I haven’t done a deep dive into its origin, but it is certainly not a reference to turntables and vinyl albums. It’s at least two centuries old and has become the standard way of referring to a righting of wrongs, a correcting of misperceptions, a definitive unveiling of the truth. It is the great temptation of the would-be memoirist; it is the lie that every journalist tells the controversial figure they’re about to interview. “Wouldn’t you like to set the record straight once and for all? I’d like to help my readers understand your side of the story.”

(A note, based on bitter personal experience: if any reporter says anything like that to you, particularly when you have found yourself caught up in a tempest, hang up the phone. Delete their emails. Block their Facebook friend request. They may not be filled with malice, but the outcome of anything you say can and will be used against you if it serves the reporter’s one true aim: an engaging story. Can I take my own advice? Read on.)

I was an historian once, and ours is a profession obsessed with setting records straight. Half the doctoral dissertations written in the field are about proving that what was once thought certain is not in fact so. When I was in graduate school, my fellow students and I were trained to look for myths to debunk. We were taught to find the flaws in the widely admired -- and find the redeeming qualities in the reviled. After a while, the whole business ends up being predictably cyclical. I was trained as a medievalist, and in my 35 years of being serious about the subject, I have seen kings like Henry II, Edward I, (and of course) Richard III go through about six reassessments each. They are criticized and cast down, only to be reappraised in a favorable light a few years later. The same is true of US presidents: Woodrow Wilson, for example, is going through a rough patch with historians, but the wheel will turn and by 2035 or so, he will be near the top of our great ones again, only to slide back dramatically around 2064.

When someone says of a public figure, “History will not be kind to them” (or the reverse), the historian grins. Historians make their reputations by contradicting the conclusions of their predecessors. Nearly every wretch will have his moment of reevaluation and redemption, not because he deserves it, but because the desire of a graduate student to say something original demands it.

(A theologian friend of mine says the New Testament can be boiled down to Jesus saying, “You have heard X,but I tell you, Y.” According to my friend, “This is how we know that Jesus did a graduate degree in history.”)

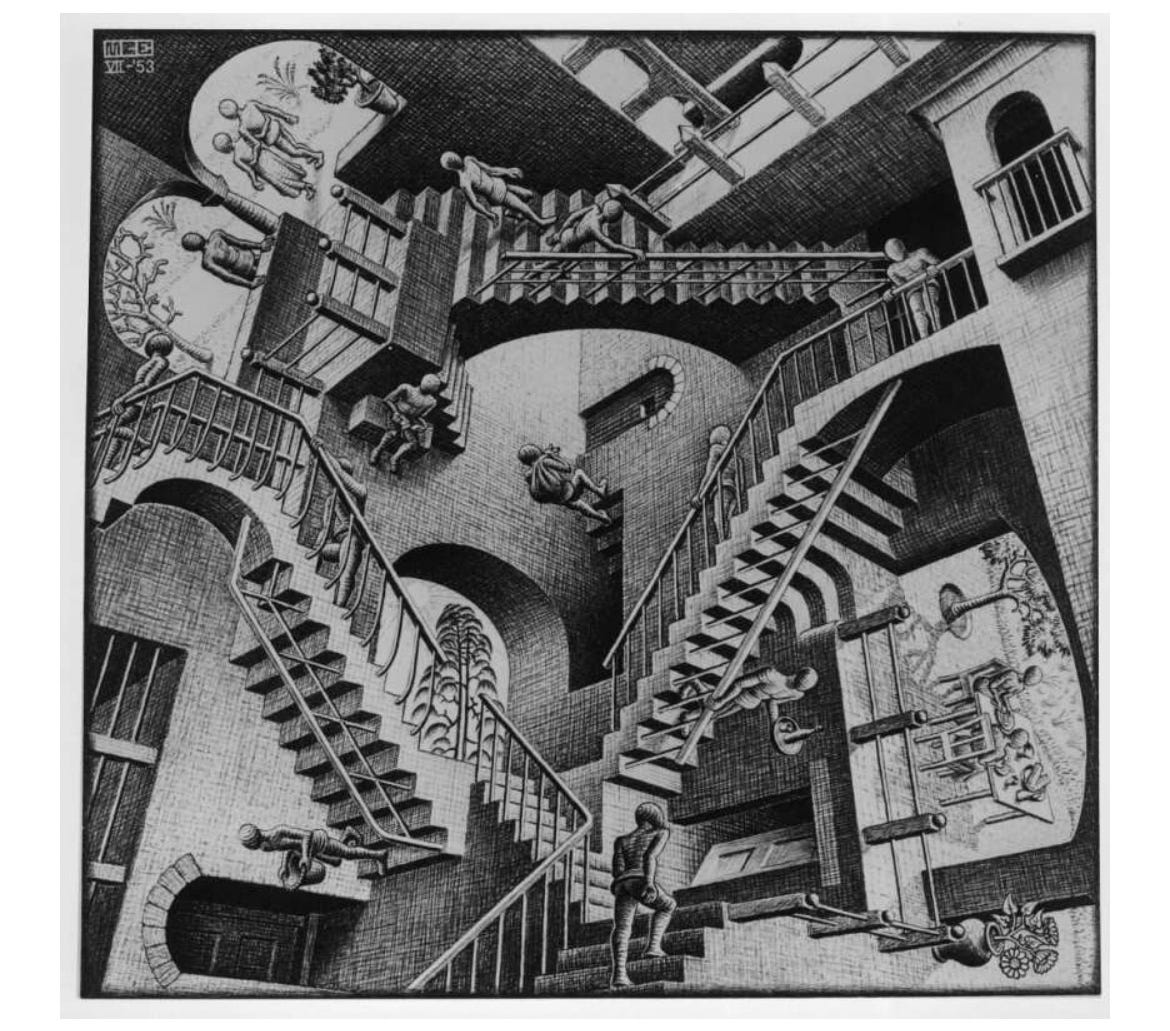

Looked at more broadly, historians consider their understanding of the past the same way a pilot flies across the country – through an endless series of course corrections. In other words, the record is never straight. This is not an argument against writing history. It is not an argument against memoir, either. It is a reminder of the limitations of both.

My great-great-grandfather, Albert Alfonso Moore, wrote his memoirs. Genealogy and Recollections was privately published in 1915, but thanks to a Mormon cousin, it has been digitized and is available for free online through BYU. A.A., as my ancestor was known, was less concerned with setting a record straight than in making sure that names and stories survived. From his introduction:

Those dead of whom I write, abhorred with all mankind the notion of oblivion – being forgotten as if they had never lived. No doubt it would have pleased much any of those dead ancestors of whom I am to speak to have known in life (if possible) that in 1915 a descendant should write the name – as Enoch, or James, or John, Polly, or Betsy – in kindly remembrance. One would rather be abused than forgotten. There is a kind of immortality in the recollection one leaves in the memory of man… Maybe I write of the past and my forefathers in slight hope thus still to be here, in the sense of being spoken of by my own people and for a time.

I’ve had occasion to question my great-great-grandfather’s conviction that “one would rather be abused than forgotten.” Albert Alfonso did not consider the horrors of Twitter. Still, his words – which many of my generation of his descendants can recite from memory – ring right. We mostly do want to be remembered, and we owe it to our ancestors to remember them as best we can and make that memory tangible in the written word. The slight hope “thus still to be here” is the plea that drew me to first to teaching history and then to ghostwriting memoirs. I want as many people to “still be here” as possible.

The issue, of course, is “kindly remembrance.” My ancestor tells kind anecdotes where he knows them, and otherwise his memoir is a great deal of “begats” and “begans.” There are no stories of adultery, of cruelty, of disappointment or betrayal. I suspect A.A. knew at least rumors of these, and because it was 1915 and because remembrance that wasn’t kind didn’t count as worthy, he left those stories out. I am none the poorer because I don’t know anything salacious about Enoch, or James, or John, Polly, Betsy, or Albert Alfonso.

A.A. Moore wasn’t concerned with setting the record straight. He was concerned simply with leaving a record in the first place, and he did that task well.

We live in a different world now. We live in a world that is simultaneously over- and under-informed. We have the library of Alexandria at our fingertips, but much of what we read is biased or incomplete. In our hyper-partisan age, everything is politicized, filtered through ideological and cultural lenses that turn yesterday’s heroes into villains. More to the point, the Internet and social media turn complex contemporary lives into caricatures. For many of us – including my current, past, and prospective ghostwriting clients – the urge to “set the record straight” is overwhelming. For a celebrity or someone swept up in a notorious scandal, the desire to say “You have heard X, but I tell you, it was all Y” is irresistible. I am glad of that desire, as it seems to be paying the bills at the moment.

I am not immune to it either. This week, the following message arrived via Instagram:

Good afternoon Mr. Schwyzer,

My classmate, xxx xxxx, Managing Editor at the Courier, and I are working on an article about PCC’s handling of hiring, firing and discipline around sexual harassment as well as the effects that the publicity around these events have had for parties involved.

Without getting into specifics, would you be interested in chatting with xxxx and I about your assessment of how PCC handled the aftermath of the harassment allegations and public response?

Feel free to take some time to consider this, but we are wondering if you would be interested in being interviewed by us. We will be utilizing trauma-informed interviewing practices and will maintain a compassionate demeanor throughout the interview.

Sincerely,

Yyy yyyyy

Features Editor at The Courier

The Courier is the student newspaper at Pasadena City College. We are rapidly approaching the tenth anniversary of my resignation from the place where I taught history for 20 years.

When I first read the note, I flared in outrage. I was never accused of sexual harassment! I confessed to affairs. None of my lovers complained or made “harassment allegations!” I must set the record straight with these two young reporters who were in elementary school when I last taught on that campus!

I care a great deal about the distinction between consensual affairs and unwelcome sexual harassment. Both may be unethical, but they are different. My internalized therapist says, “Dear boy, you care about this distinction because you want it on record that you never needed to foist yourself on anyone. Your ego needs it to be remembered that your great mistake was ‘not saying no,’ and that you were an object of young women’s desire even into your mid-40s. You think being a harasser would be beneath you, while being a weak-but-charismatic lecher is a more pleasing image. Setting the record straight is about your own self-regard.”

I argue back with that internalized therapist: “It may serve my ego, but it also happens to be true. I don’t want to let a lie live on. I must talk to these reporters so that they know the truth!”

I am obsessed with getting the story straight about how I lost my job. My trauma and my ego battle with my own keen awareness of how history, journalism, and public image work. I know that it is a losing game to give interviews. I have advised clients against it. (At least until the book comes out.) It is so danged hard to take my own advice.

I am no theologian, but it strikes me that the spiritual highpoint of the entire New Testament comes in 1 Corinthians 6:7:

The very fact that you have lawsuits among you means you have been completely defeated already. Why not rather be wronged? Why not rather be cheated?

Why not rather be wronged? Why not rather let people believe what they are going to believe? Why not stop trying to set the record straight? I know instinctively that my own mental health hinges on being able to stop litigating the story of how I lost my job. If I can get to the place where half-truths and misconceptions dominate the narrative, and I can be at peace with that… then, surely, I will be free.

I tell my clients, “I cannot guarantee you that everyone will believe what you say. I cannot guarantee you that ours will be the definitive record of your life. I can guarantee you that I will do my best to make it so.” I tell those who pay me, “I write with a keen sense that your children and your children’s children’s children are also my clients. At the same time, others will tell their own stories about you, and their memories, once written or said aloud, will curve and bend the record. You cannot control that.”

“God writes straight with crooked lines.” So said Thomas Merton, or St Augustine, or St. Theresa of Avila; the origins of the aphorism are disputed and murky, like our lives themselves. The comfort in those words, for the believer, is the reassurance that whatever mess we make may still be used for the good. For the historian or the journalist or the ghostwriter, the reminder is that anything we scribble will be incomplete. It is not that there isn’t a truth about, say, why Hugo Schwyzer was forced to resign, or whether Woodrow Wilson was a bigot, or whether Richard III really murdered those little princes. It’s that our certainties themselves, even if they are rooted in research or memory, are bound to be crooked.

The record will never be straight. It is worth telling the story anyway, as long as you can bear that it will be disputed, or mocked, or ignored.

I have not yet decided whether to write those journalists back.