All the Angry Totalizers: Super Bowl Thoughts

On a hot Sunday afternoon several summers ago, the children and I sat at Toppings Yogurt. Toppings is a staple in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood, itself the heart of Orthodox Jewish life in Los Angeles.

There were two tables in Toppings. The kids and I sat at one; a large family of seven crowded around the other. Their clothing marked them as “frum” – fully observant Orthodox Jews. There was a mom, a dad, and five young children. Mom appeared to have a sixth on the way.

Toppings is on a busy street; most of the clientele are religious Jews (the offerings are of course all kosher), but on warm days, all sorts of passers-by stop in. This day, two teen girls bounced through the front door, each in very short shorts and skimpy tops with spaghetti straps. The frum family looked up, and after only the briefest of glances at the teens, the bearded father pivoted in his chair, turning his back to the new customers. He picked up his youngest, and they giggled together.

The teen girls didn’t notice the shifted seat. My kids didn’t notice. The frum kids and their mother didn’t notice. The father deftly averted his gaze in a way that honored his faith without causing shame or embarrassment to anyone. He knew what his responsibility was -- and what it wasn’t. His job was to look away, not to condemn or mock or judge. It was a small yet impressive demonstration of pluralism.

There is no unifying event in American life akin to the Super Bowl. It is the most-watched event of the year; in this age of everything on (varying) demand, it can only properly be enjoyed live, with millions experiencing the same sights at precisely the same time. Some care most about the game; some care most about the commercials. Some care most about the snacks; some care most about the halftime show.

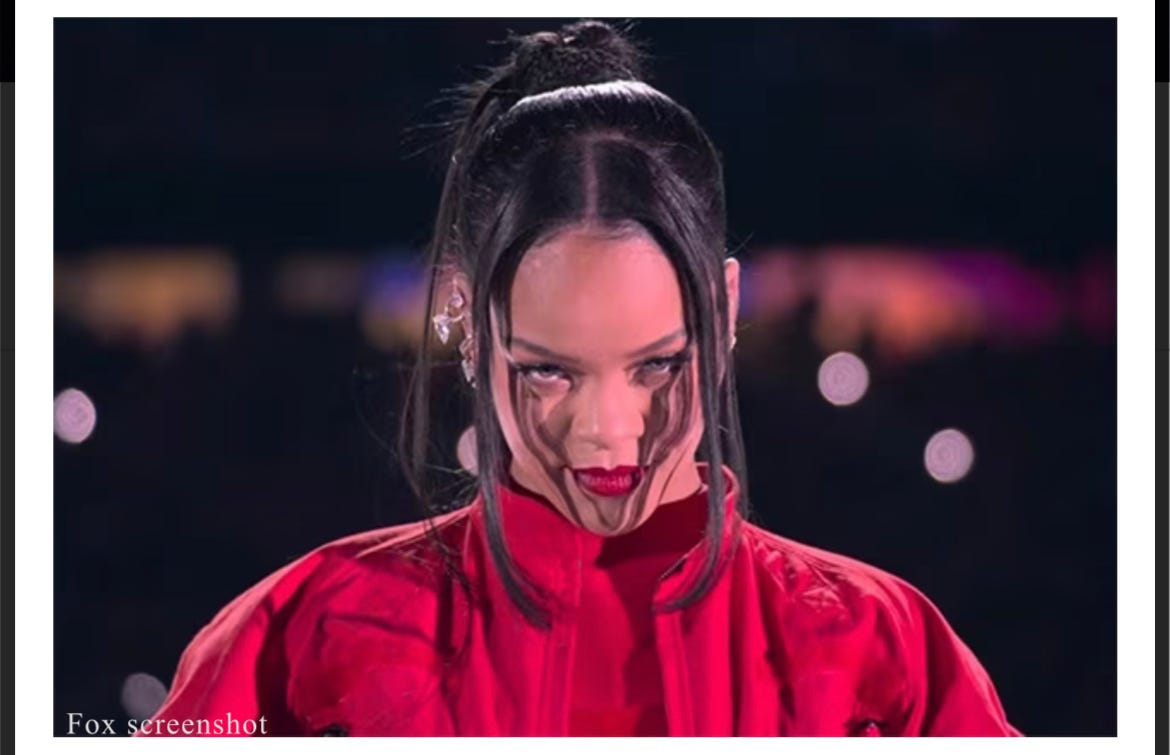

For such a gaudy and brief spectacle, Super Bowl halftime shows are a massive blank slate on which we can all scribble our opinions. We’re all watching the same thing. We don’t have to explain context or send a link to get our friends animated; the halftime show offers an increasingly rare simultaneous experience, and we are desperate to share our opinions. “Is Rihanna pregnant?” “Last year’s show was better!” “This is obscene!” “Why is she dancing with Teletubbies?”

A scarlet tabula rasa

The outrage began long before Rihanna ascended into the upper reaches of State Farm Stadium.

Once the show began, the negative reactions ranged from the absurd to the resigned.

When Congressman Dan Crenshaw (R-Tx) tweeted out his admiration for Rihanna’s performance, he got vehement pushback from social conservatives upset with his praise.

Meanwhile, the frum just shifted their proverbial seats:

An ad for a frum halftime program.

The most hardline of the Ultra-Orthodox won’t watch any television. There are plenty of more moderate (TV and smart-phone-owning) groups, including a great many who are willing to watch the NFL – but not a risqué halftime show. Orthodox Jews don’t spend time attacking Rihanna, or Sam Smith’s Grammy performance. They already know these sorts of spectacles are not for them. The strictures of the Torah are for Jews, not for the entire planet. You won’t get most Orthodox Jews to condemn Rihanna’s performance any more than you’ll get them to demand the stadium only sell glatt kosher hot dogs. To be a religiously observant Jew in America is to practice radical commitments without expecting others to share them.

Mainstream Orthodoxy says, for us watching the NFL is okay, watching the halftime show is not. All the rest of y’all get to do whatever you like; we’ll join you for the second half after we hear a good Torah message. It is intense commitment combined with an almost genial relativism.

Judaism is not a missionary religion. It does not seek converts. It does not believe God has called everyone to the same set of conclusions. Christianity, of course, is very different. Christians are called to build societies that honor Christian values; most serious Christians would like it very much if more people lived and believed as they did. No Jewish leaders want America to be a Jewish nation; plenty of Christian leaders do want America to return to its Christian roots. That’s not because religious Jews are more committed to pluralism – it’s because religious Jews have, to put it mildly, a completely different historical relationship with the state than do American Protestants. Holding up the former as an example of how the latter should behave is a cheap rhetorical trick. It’s just not that simple.

I find much to admire about the quiet way that frum father shifted his gaze. I find much to admire about those who organized a Torah program during the Super Bowl halftime. I’m a natural libertarian: Instinctively, I prefer “In our family, we don’t think we need to see Rihanna rubbing her crotch so we’re going to do something else” to “We need a moral awakening in this country so that no one is allowed to rub their crotch on TV anymore.”

I also know that the freedom to live a frum life and to raise one’s children in the faith is a tenuous one – and increasingly, it is protected by some of the very people most vocal in their outrage over the likes of Rihanna.

Last year, an appeals court ruled that Yeshiva University – the flagship school of Modern Orthodoxy in the United States – “must formally recognize an LGBTQ student group, rejecting the Jewish school's claims that doing so would violate its religious rights and values.” The case is likely on its way to the Supreme Court. Joining Yeshiva in its appeal are a host of conservative Christian organizations.

For Orthodox Jews, the Yeshiva case is a reminder that respect for other people’s commitments is not necessarily a two-way street. Those who want full inclusion for gays and lesbians and trans folks will not stop at the synagogue door, or at the gates of the only major Orthodox university in the country. The genial détente of “You do you, and please let us do us” isn’t viable any longer. It’s one thing to avert your gaze in a public yogurt shop or to find a spiritually uplifting alternative for halftime. It’s another to be told that your private spaces must now adhere to a very different kind of orthodoxy.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, one of the most common chants at Pride marches was “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” In an era where same-sex marriage was unthinkable and sodomy laws were still enforced, it was a plea for tolerance couched in the rhetoric of a demand. Of course, as any historian could tell you, the most flexible word in that chant was “here.” It’s one thing to ask to march the streets of San Francisco, wed your best friend in a civil ceremony, or make love in the manner of your choosing in your own home. It’s another to demand that a private, Orthodox Jewish university affirm those choices. There’s a difference between the “here” of the street, and the “here” of Yeshiva University.

Both the secular left and the evangelical right are reluctant to let there be any “here” in which their values are not ascendant. Conservative anger at the Super Bowl halftime show or the Grammys is rooted in a frustration that a culture that Christians once mediated is slipping from their grasp. Lefty anger at bakers who won’t make cakes for a gay wedding, or at religious schools that won’t permit LGBTQ clubs, is rooted in a frustration that parts of the culture refuse to accept the new sexual orthodoxy. Here needs to be everywhere, and we cannot rest until the battle is won!

Sex, of course, is not the only battleground for totalizers. Many on the woke left are anguished that the Super Bowl-winning Kansas City Chiefs continue to use Native American imagery, tomahawk chops and chants.

The tweeter here, Simon Moya-Smith, offers a long piece in the Nation calling for an outright ban on the chant and the name. It’s not enough to ask people to reconsider their choices, not enough to change the channel – no, the NFL must prohibit the chant and chop, with expulsion from games as an immediate consequence for future violations.

I understand my friends who are worried about a hypersexualized culture. I understand my friends who are worried about racist imagery. I understand my friends who want to be affirmed for what they are, and I understand my friends who want a space in which such affirmations are not compulsory. I know it’s a lot to ask, and it’s probably not an enduring solution, but perhaps the next time you are confronted by whatever seems expressly designed to offend, you might, if only for a moment, decide you aren’t going to rise or tweet in eloquent indignation.

That father in the yogurt shop got something right about American life, and I think of his example often.

Can we really know what motivated that man to turn around? If a Christian pastor did it, would you have seen it as snobbish - a sign of your most detested emotion, disgust? Personally, when I read about your billionaire friend who didn’t buy coffee for you - and you assumed it was to protect your dignity - I was angry (for you!). By all means, he should have paid. You wrote something like, “I could tell he was trying to consider whether he should offer to pay.” But we do not really know what motivates others. Could be the same reason the mega rich often refuse to tip.