On November 1, 1986, late in the fall semester of my sophomore year at Berkeley, the California Golden Bears fired head football coach Joe Kapp. After five mediocre seasons, the university had tired of Kapp’s antics, many of which were worsened by a well-known drinking problem. Yes, he was a beloved alumnus who had led us to our last Rose Bowl appearance. (And remains the only quarterback in football history to start in the Rose Bowl game, the Grey Cup, and the Super Bowl.) Yes, Kapp was charming, roguish, and adored by his players. His off-color remarks and heavy drinking would have been tolerated if the Bears were winning, but the team had just clinched their fourth consecutive losing season. After a 27-9 loss to Oregon, Cal’s athletic director announced that Kapp could finish out the year, but that would be it.

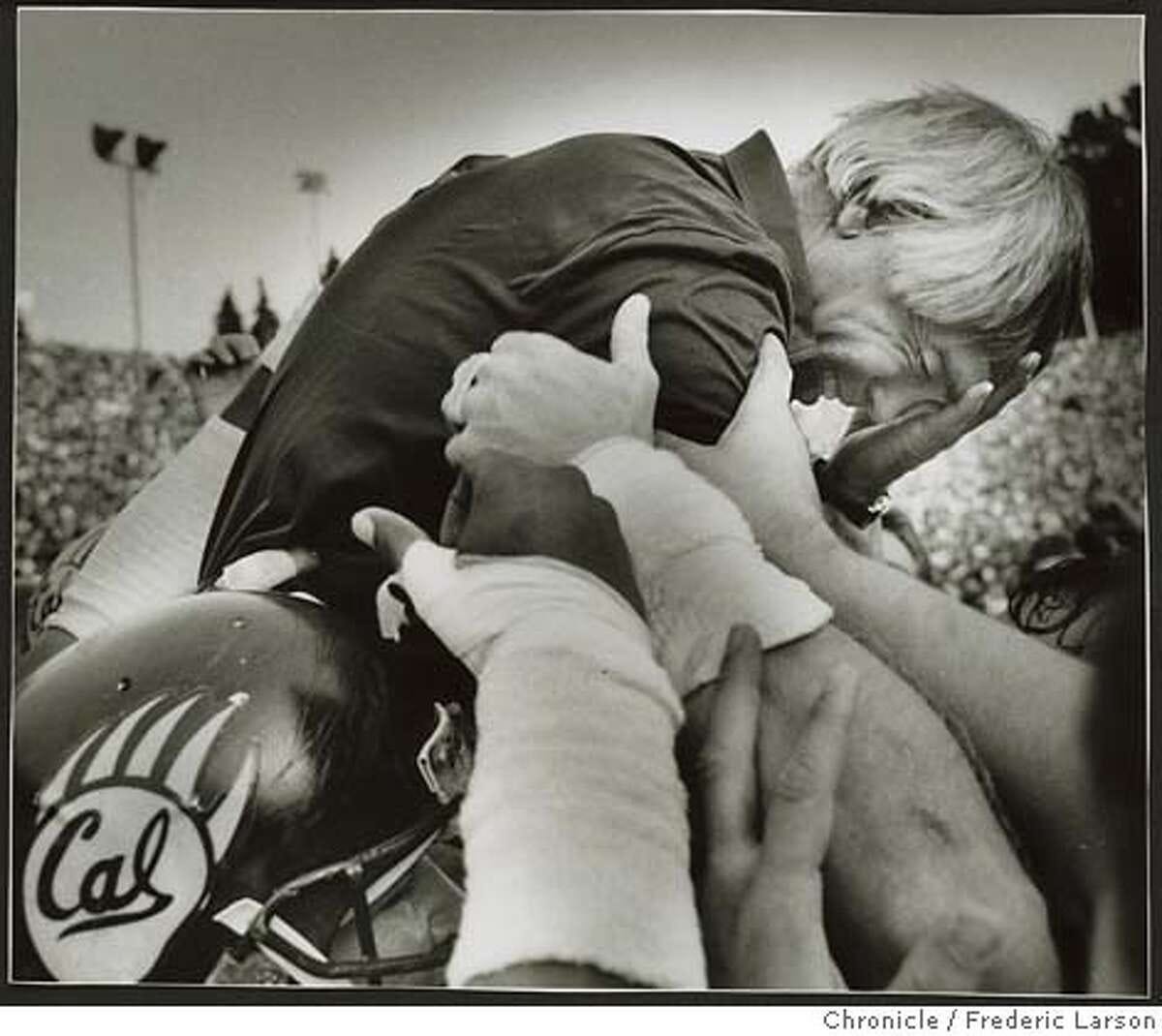

On November 22, Kapp coached for the last time as our Bears hosted Stanford for the Big Game. Stanford had clinched both a winning season and a bowl bid; Cal was playing their archrival for nothing but pride. My 19-year-old self was there as we upset Stanford, who were double-digit favorites. A jubilant crowd took the field at the end of the game; Coach Kapp was carried off on the shoulders of his players. He was sobbing.

At the post-game press conference, the reporters grilled coach about his strategy – and his regrets as he looked back over his tenure. Kapp was weepy and exhausted, but he took each question as it came. At last, Hardy Nickerson – our star senior linebacker who would go on to a long and illustrious NFL career – came into the room, stepped on to the dais where Kapp sat, and tapped him on the shoulder.

“Enough of these people, Coach. Come where you’re appreciated.”

Kapp stood up, and walked, arm in arm with Nickerson, back into the locker room.

Joe Kapp, breaking down as he is carried off the field after coaching his last game, a 17-11 win over Stanford. I’m about 20 yards away, screaming in joy. November 22, 1986.

Yesterday, I listened to a podcast conversation between Meghan Murphy and Jamie Kilstein. Unless you’re a very online feminist, these are perhaps not names you recognize: Meghan is an old friend famous for what she once described as “no-fun feminism.” Meghan is deeply suspicious of the trans movement, and favors a ban on pornography. Jamie and I were once two of the best-known “professional male feminists” in America. Jamie had a successful comedy career and a radio show; we were, in different but not dissimilar ways, the straight male darlings of the feminist blogosphere of the mid-to-late aughts and the very early 2010s.

Jamie and I both had precipitous falls from grace. Each of us was accused of sexual misconduct, though nothing that rose to the illegal; I confessed to sleeping with students, while Jamie was accused by his former wife (and radio cohost) of a series of extramarital affairs. Not exactly Jeffrey Epstein in either case, but for two men who had built brands on self-righteousness, sensitivity, and honesty as well as egalitarianism, our behavior fell gloriously short of the male feminist mark.

Jamie struggled with despair and suicidal thoughts after his cancellation. He struggled with shame. He struggled with the fact that all his former friends and colleagues wanted nothing more to do with him; that he was persona non grata where he had once been welcomed.

That was my story too. I chose, eventually, not to have a public life. I chose ghostwriting and retail. As he told Meghan, Jamie did find a way to stay in comedy and radio – but realized quickly he would need a different audience. He found receptive listeners on the right, or at least the libertarian center. An appearance on the hugely influential Joe Rogan Show led to dozens of invites to appear on conservative podcasts. Jamie always accepted, explaining, “I’m not a conservative. Just because I was cancelled by the left doesn’t automatically make me a right-winger.” Invariably, he would be told he was welcomed anyway.

Jamie has not become a man of the right. He has simply, by virtue of his cancellation, become free to express views that were anathema to those who were once the source of his livelihood. (For example, Jamie has become convinced that pornography is deeply deleterious to men, and he is skeptical of the trans rights movement – two issues that created a common bond with Meghan Murphy.).

On the podcast, Jamie talked about how astonished he was to be welcomed so enthusiastically and warmly by Christian conservatives. “I’m this Jewish lefty and they know who I am, and they know I swear in my comedy and they’re still being so nice to me.” He did not, to his credit, feign an instant political or spiritual conversion to win an audience; he didn’t attempt to launch a show to compete with Ben Shapiro or Dave Rubin -- two well-known, relatively young, popular Jewish conservatives.

It was just nice, Jamie said, to go somewhere he was appreciated.

In the immediate aftermath of my fall in 2013, a handful of somewhat well-known Christian conservatives did reach out to me. A few were interested in seeing if I would provide them with a quick-and-easy conversion story. “He used to teach a class on porn, but now, he warns of its dangers!” I jokingly replied that to paraphrase the most famous hymn of all, “I have been lost several times, repeatedly declared I could now see, only to stumble into further blindness. I have been lost and found more often than your grandmother’s eyeglasses.” At some point, trying to sell yet another redemption story is both an obvious grift and ipso facto evidence of shamelessness.

And yet, there is something to be said for going where you’re appreciated. We’re familiar with the stories urban lefties promote, stories of queer kids who escaped from small-town Christian bigotry to find a place where they are accepted. Everyone deserves a welcome, and the left loves to tout its welcome to those whose choices (or very identity) cause them to be cast out of conservative communities.

The same left tells men like me (and Jamie Kilstein) that our cancellations were not the result of bigotry but richly deserved consequences for our misdeeds. “To go where we are welcome” – meaning to the right – would simply prove that we either remain unrepentant or that our previous claims of solidarity were indeed just a grift or an act. I can’t tell you how many progressives have told me, often in gentle tones, that it would be good and right for me to work retail for the rest of my days.

Both Jamie and I heard the same line: “You don’t get your second chance until everyone else has had their first.” We were both reminded we were privileged white men, and to the extent that our redemption was possible, it could only happen through falling silent and allowing others to step into the spaces we had once held.

There was another message too. “Don’t you dare go where you’re appreciated.” If you go where they will welcome you, where they will give you a second chance, you might be, as Steve Winwood sang, “back in the high life again” – but at the cost of your very soul. To the cancellers, only a lifetime of Sisyphean penitence, defined chiefly by shutting up and abjuring any public life or chance at comfort, would be sufficient.

Eventually, you learn that the people who cancelled you won’t uncancel you. The doors they closed won’t open up again, even if you knock loudly with extravagant pleas, so if you want to ever get out of the hallway, you need to go through a new damn door.

On that November afternoon so many years ago, Joe Kapp was willing to stay until the bitter end, fielding questions from a hostile press, reliving his mistakes, confessing his shortcomings. A young man who loved him asked him to stop talking to those who would never understand -- and come be in the arms of those who would.

Coach got up, and walked through a door into another life.

I think of his example often, and I am not ashamed that increasingly, I am doing the same.

A dear friend from HS who decided to "come out" (c'mon, we all knew) while at college went on to become a very successful professional and eventually be able to marry his long time male lover. After a large disaster in my small town he mailed a very large check to the local fundamentalist Baptist church there to be used as they saw fit. He was Catholic. He was asked why he, an out, gay Catholic would donate to such people. His answer basically was that when he was at his most down time in HS and early college the people of that church remained his friends, held him up, and reminded him constantly that, "Jesus loves you" and so did they. That got him through his most trying period.

He says they really did love him, and it probably saved his life.

Come on in, the water's fine.