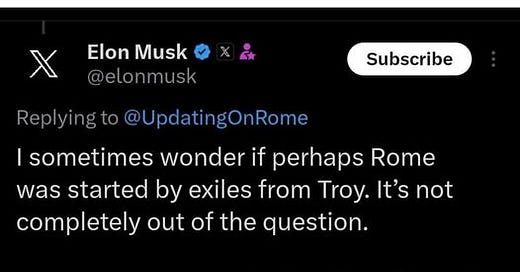

Elon Musk has not read Virgil’s Aeneid. On Monday, the mercurial billionaire tweeted:

(There’s a context for the tweet that you may have missed. Earlier this month, a challenge went viral on TikTok and other social media apps. Women were encouraged to ask their husbands and boyfriends, “How often do you think about Ancient Rome?” Wives and girlfriends were, we are told, shocked to discover that a great many men spend a lot of time thinking about what happened in Southern Europe in the twelve hundred years between the mythical Romulus and reign of his hapless namesake, Romulus Augustulus.)

People made fun of Musk’s tweet. How does someone care so much about Rome and yet not know its central origin story? Or perhaps he does know the origin story — a Trojan refugee named Aeneas shows up and marries a local — and instead of regarding it as a myth, he has convinced himself it’s true? In either case, what an idiot, right? Better to be silent and thought a fool than to tweet this and remove all doubt!

I have a soft spot for Virgil. My doctoral dissertation at UCLA was entitled “Arms and the Bishop,” a play on the opening words of the Aeneid. (Arma virumque cano, usually translated as “I sing of arms and the man.”) I taught ancient history for twenty years, lecturing every dang semester on Rome’s self-conscious mythmaking and comparing it to our own. I’m hardly a classicist, and my Latin is rusty, but I could probably still give a lecture on the Second Triumvirate, or the Five Good Emperors, or Julian the Apostate should someone demand it. And so, I wanted to mock Elon too. That was not me at my best.

I am fascinated by what other people consider to be “common knowledge.” When I started work at Trader Joe’s in 2017, I had no idea what to do with a pallet jack. The young woman who taught me how to deploy this essential warehouse tool looked at me and said, “I can’t believe you’re fifty years old and you don’t know how to use one of these.” I might have replied, “Miss, I can read Anglo-Norman French and koine Greek. I can recite Shakespeare and Goethe and Mill. I know which fork is for fish and which for cake. My kind of people did not grow up learning about pallet jacks.” But of course, that would have been a stupid, snobby, indefensible thing to think, much less to say.

I gave the only possible reply. “You’re right. I’ve left it late. Thank you for teaching me.”

I was raised in a world in which common knowledge meant knowing a lot about European history, European literature, European music. One might become an academic and specialize in one thing, but one was expected to retain an inner taxonomy of What Is Important and What Is Less So. A gentleman is allowed to be apologetically helpless at the prospect of changing a flat tire. He is not allowed to not know who Virgil was, even if the specifics of one particular long poem elude him.

(Tom Wolfe nails this in Bonfire of the Vanities: “The only thing that had truly stuck in Sherman's mind about Christopher Marlowe, after nine years at Buckley, four years at St. Paul's, and four years at Yale, was that you were, in fact, supposed to know who Christopher Marlowe was.” I’d add that a gentleman is supposed to know the historical origins of the bonfire of the vanities and be prepared to shake his head sadly as he recalls the cruelties of Savonarola’s Florence.)

I’ve spent enough time working in grocery stores and warehouses and accountants’ offices to know that common knowledge is a concept bound by class, culture, and perceived necessity. If we spent the day with a group of coal miners, or a band of cryptocurrency investors, or a gaggle of bluegrass musicians, we would hear words and terms we did not understand. If we were bold enough to ask a question, we might be indulged – or ridiculed for not knowing something so basic.

My family no longer marks the high holidays. On Yom Kippur afternoon, I drove my daughter to a friend’s house, and Heloise studied the observant as they walked to their various synagogues for the climactic Neilah service. Based on footwear, sleeve length, and headgear, my child expertly decoded where each person fit on the spectrum from Reform to Haredim. In Heloise’s world, understanding that modern Orthodox women will wear three-quarter sleeves while Chassidic women will cover to the wrist? Common knowledge! Who doesn’t know these things?

Most people don’t know these things. And that’s fine, just as it was fine for me to never use a pallet jack until I was fifty.

I understand the temptation to look at our fractured and divided nation and say, “It’s so dreadful that we have no common knowledge and no common culture.” I understand the impulse to mock the richest man in the world for offering up an ancient idea as if it were his own. I understand the desire to demand a common core, a shared knowledge base, so that we can all recite Virgil together; or distinguish the baroque from romantic; or understand how to properly wield a box cutter, a jackhammer, a pallet jack.

Yes, our schools should still teach civics and literature. I would rather like it if my children know who Marlowe and Virgil are. But I am far more concerned with their willingness to learn what they do not know, and their willingness to ask the right questions when confronted with a gap in their knowledge and understanding of the world.

In Howard’s End, E.M Forster gives us two families to consider: the artistic, educated Schlegels, living on inherited wealth — and the nouveau riche, brash, striving Wilcoxes. It’s clear that Forster considers himself a Schlegel, and most of his readers are “Schlegels,” but we’re not invited to mock or sneer at the philistinism of the hard-driving Wilcoxes. Instead, Forster forces us to see that each family has much to teach the other.

At one point, Margaret Schlegel, reflecting on her own snobbery, muses to herself “How dare Schlegels despise Wilcoxes, when it takes all sorts to make a world?”

Our great modern problem is that we don’t believe that those who are different from us are helping us make a world. Rather, living in our siloes and bunkers, we are told over and over again that the other side is (through malice or ignorance or both) hell-bent on erasing everything we hold dear. The modern version of Howard’s End would read, “How dare Schlegels even speak to Wilcoxes? Do they not see that Wilcoxes are destroying our world?”

I could probably teach Elon Musk something about Rome. He could teach me a great deal more, about cars and tunnels and rockets. If I tweeted something about spaceships that sounded smart to me (but ridiculous to a rocket scientist), I would rather not be mocked. I’d like to be corrected and invited to indulge my curiosity by learning from an expert.

Very few of us are going to be polymaths, mastering dozens of intellectual disciplines. Despite the keen awareness of our shortcomings, few of us can resist the urge to roll our eyes when someone reveals they do not understand something we regard as basic and essential. It is a powerful temptation, but one that ought to be resisted, nonetheless. Hubris and hatred are greater threats than error.

The people who don’t know Virgil but do know rockets have a part to play – as do those for whom the reverse is true. It takes all sorts to make a world.

Musk is a technocrat and I doubt he knows very much of the very businesses he's in. His family part of the apparatchiks like Gates' that treat them like spoiled brats but force them into slavery for the elite globalists. He probably wouldn't understand anything about all that you studied really. He'd just know the parts that kept the oligarchs in power or destroyed them. They've had to morph, shape shift when found out (they hid in Venice for awhile) and then emerge again like the pirates they are. When the going gets rough, as I think is on its way, knowing the basics will come in handy but who knew we'd have to learn how to garden, change a tire, fix a motor while knowing all that glorious other stuff you know. It all matters but we're headed for the basics for awhile if Musk's funders have their way. Being humble always pays.