The Cousin Who Fell Off the Mountain: On Family and Memory

This is a free post, available to all. For the full experience, and additional posts, please consider a subscription. Thank you!

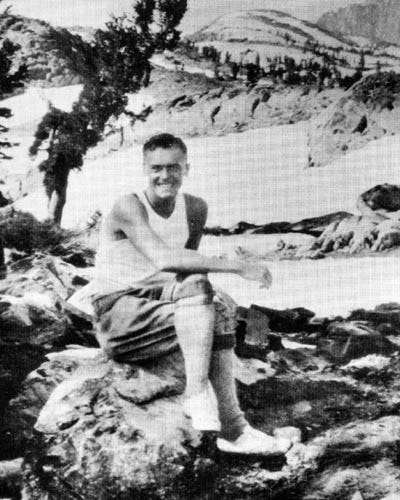

Pete Starr (1903-1933)

“Are we related to any famous people?” David asked recently, curious and hopeful.

His father, grandfather, and uncle all have Wikipedia entries, but that won’t impress him much. Another relation was a moderately well-known TV actor, but on shows that had been off the air for decades before my son was born. Little House on the Prairie, for all its cultural resonance, has no meaning (yet) to David.

I tell him about cousin Pete. “One summer day, 88 years ago, your cousin went into the mountains to climb. And he never came back.”

David’s eyes grow wide, as mine did when I was his age and first heard this story that is at the heart of family lore.

Pete Starr was born in 1903. He was my grandfather’s first cousin, the son of my great-grandfather’s beloved sister. His real name was Walter Augustus Starr, Jr., but everyone called him Pete. (He was lucky, in a sense – other family members of his generation went through their entire lives with nicknames like Muffy, Bunt, and Tubby.) He grew up in Piedmont, California – and on a ranch in the hills above Mission San Jose. The legendary architect Julia Morgan designed and built the house in which Pete spent much of his childhood; it now belongs to my cousin, also a Peter Starr. Pete and his brother Allen were very close to my own grandfather, and they played and rode together every summer of their youth.

Pete broke family tradition by going to Stanford instead of Berkeley. (He kept family tradition by joining Deke). He ran track, and had a reputation as a marvelous dancer, writer and pianist. By the time he was 26, Pete was practicing law in San Francisco – and infamous as one of the Bay Area’s most eligible bachelors.

Pete’s father had been one of the founders of the Sierra Club. Pete himself first came to the Sierra backcountry as a boy, and there found his great passion. He chose peaks and precipices over horses and cattle. Pete soon became first a master climber, and then a legendary one. He climbed without a rope, a pack of Chesterfields in his shirt pocket. He wore tennis shoes and khaki trousers even on the most difficult of ascents. Before his 30th birthday, he had climbed every major peak in the Sierras and made a very successful trip to the French Alps. He had also mapped out the recently opened John Muir trail, and had begun to write a guidebook.

Pete was willing to explore the mountains with others, but this otherwise most sociable of men was happiest when climbing alone. And he was very much alone on July 29, 1933, when he left a friend’s wedding party to drive to the Minarets, a formidable denticulation in the central Sierras. Pete was supposed to return within ten days. He never did. Because of his fame and the family’s prominence, his disappearance garnered considerable media coverage – and the first-ever aerial search for a missing person in the Sierra Nevada. Eventually, the legendary climber Norman Clyde, a long-time friend of my cousin and one familiar with his habits, decided to intuit what Pete might have been planning.

After a day searching in the Minarets, Norman Clyde found the body at the foot of Michael Minaret. Pete had clearly fallen several hundred feet and been killed instantly; he was found on his back, arms stretched over his head, a peaceful expression on his face. It would have been impossible to carry his remains out – and Clyde knew that Pete would far rather rest forever in the mountains than in a city cemetery. The older man built a cairn of stones over Pete’s body, and it remains there still, inaccessible to all but the most skilled and curious of mountaineers.

That’s the brief sketch of Pete’s short life and sudden death. You can read more about Pete Starr; order his guidebook here; or get the book (written with the help of various relatives) about Norman Clyde’s search for the fallen legend.

Last week, I told David about Pete, his first cousin, three-times-removed. I told the story much as my mother had told it to me. My mother herself got the story differently. She heard it first from her own father -- Pete’s first cousin, who had been very much there to witness both the search and the family reaction to the dreadful news. This is how family stories work: one generation experiences a tragedy or a wonder, and they pass on the story to their children. In turn, those children pass it on to the next generation, embellishing and editing as humans do. Within a blink of an eye, everyone who was there for the original event is gone. Most stories vanish at this point, or are remembered as incomplete fragments, e.g.: “Grandma always used to say her own father rode with Teddy Roosevelt, but I’m not sure of the details.” The young are tantalized by these legends, and press for more information, but there’s rarely more to be had.

Pete’s story survives in our family because we have more than living memories on which to rely. There was press coverage at the time; there have been books about him since. There are long-standing rumors of a documentary, and I’ve daydreamed about writing the screenplay for a film. We have resources beyond our own recollections to which we can point. Stories survive because they are worth telling – but they survive better when there is something to tell beyond a departed ancestor’s half-remembered anecdote. Pete Starr wrote things down, and people wrote things down about him, and thus he will live on in the memory of at least one more generation.

Pete’s cousin Muffy Valentine Albert was born in 1919, and died in 2011. She was the last person who knew him well; she was well into her teens when he disappeared. When she died, the last person who had lived through the story was gone. My son David was born in 2012, the year after Muffy left us – and so he becomes the first person to learn the story after the final person who had met and loved Pete had slipped away. Somehow, that strikes me as significant; the Pete Starr legend has cleared a hurdle that most family stories do not.

I spoke to mama this week about what she remembers of Pete’s parents and siblings, and how they spoke of the loss. WASP traditions about restraining one’s grief were formidable; my mother said that while the story was widely known, and not infrequently discussed, the emphasis was always on Pete’s abilities as a dancer, a musician, a lawyer and an athlete. How he died was on the table for conversation – how his death impacted everyone, particularly those closest to him? That was kept quiet. It wasn’t that we as a family were embarrassed by grief. It was a sense that grief is perhaps the most deeply private emotion of all. You would no more expect someone to break down in public than you would expect them to stand up and pee on the dinner table. Heartbreak is real, trauma is real, but it is also something that most of us would rather work out behind closed doors, and those who knew Pete best and grieved his loss hardest presumably did just that.

What was remembered was that Pete embodied the family masculine ideal to an exceptional degree. He was well-mannered, talented, handsome and successful. He was also an outdoorsman. He was at home in both town and country, and not just at home, but a meteor in both universes – a charmer at the most treacherous of society parties and a skilled mountaineer on the most jagged of peaks. Pete was the consummate gentleman, and because he died still young and handsome and apparently unflawed, he has remained an unblemished paragon in family lore for nearly a century.

Pete was also, of course, a cautionary tale; our Icarus, flying too close to the sun. An older and wiser man might have thought better of freeclimbing a sheer mountainside in his tennis shoes. Pete’s death was both needless and beautiful, a consequence of both foolhardiness and destiny. A gentleman should live in tension between his calling to dare great things, and his duty not to break the hearts of his loved ones – in his brief and remarkable life, Pete did his best to balance that tension as long as he could. In the end, he could not hold on to both obligations, just as he could not hold on to the side of Michael Minaret.

My mother sends me two stories about Pete that she heard from her father, and having shared them with my children, I finish this tribute with them.

Going back to the early years of the last century, the Fourth of July has always been an important family holiday, on par with Thanksgiving or Christmas. For decades, it was traditional for the teens of the clan to put on skits before the fireworks for the amusement of their elders. Pete was a fine songwriter, and at age 13, wrote and directed a short play in which my mother’s father (then 9) and a host of other cousins performed. Rather than a patriotic theme, it involved the story of an elopement, in which Pete played the part of a groom helping his young bride escape the family home.

My grandfather and his cousin Allen (Pete’s younger brother) sang while Pete helped his “bride” (played by cousin Jill, already over six feet tall in her mid-teens) down a ladder from the roof of the ranch house. My grandfather taught my mother the lyrics he had never forgotten:

Another bird flown from the nest

My daughter Oh my daughter!

My dear sweet child, my last my best

My daughter Oh my daughter!"

When mama sang the song to me, she sang it to the tune of “On a Tree by the River (Titwillow)” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado, but there was once another tune, composed by Pete and lost to memory. This Fourth of July will mark 105 years since that 1916 performance, and all who were there are long gone, but I can still sing the words and describe the scene to my children.

The second story was one my mother heard directly from her Uncle Walter, Pete’s father. One morning in about 1911, the family car broke down on the ranch road. Everyone got out to see if they could fix it, or at least push it out of the way. At one point, an enormous dog approached. Allen, then only four, grabbed his brother, who was about eight. “Is that a wolf, Peter?” Allen asked, close to tears from terror. Pete shook his head, and explained it was only a dog that wanted to say hello. Allen, comforted, turned to the assembled adults, and announced solemnly, “Peter tells me everything I know.”

More than a century later, Pete is still teaching.