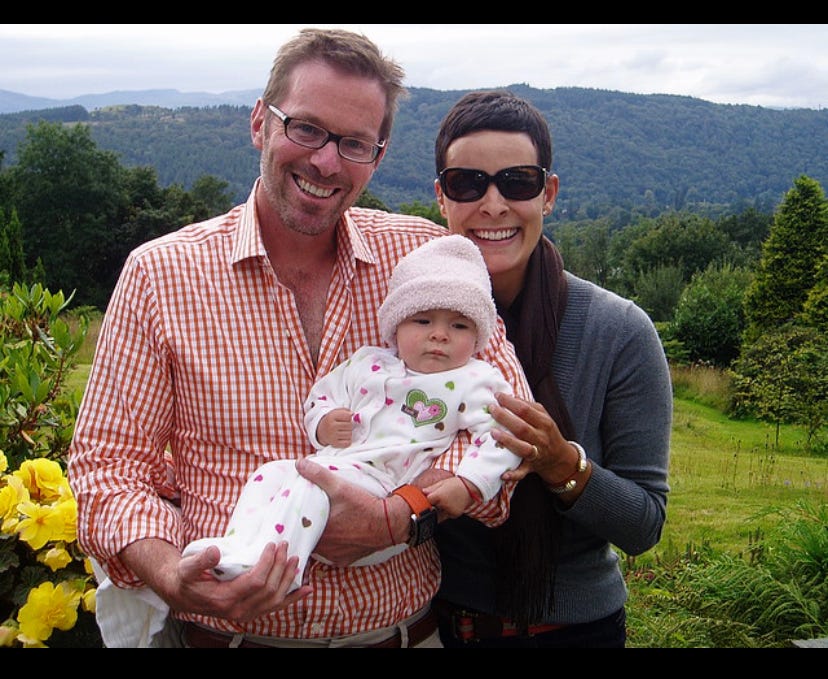

(With Heloise and Eira, in the Lake District of England, August 2009. )

If ever any two people were well-positioned to be parents, it was us. By the time we got around to conceiving Heloise, thirteen years ago this month, friends and family had been nagging us for years about having babies.

In May 2008, I was just turning 41; Eira, 33. I had tenure, and I taught a full load of classes plus summer sessions; I was bringing in $130,000 a year from teaching alone. We had excellent health insurance through the college. Eira’s various business management clients were thriving, and her income easily exceeded mine. The mortgage on our three-bedroom Pasadena condo was $1150 a month.

We didn’t exactly have money to burn, but we lived well.

We had been together six years, married for three. I had a decade sober. We had the ideal financial and relational prerequisites to be parents, as our loved ones constantly reminded us. My mother didn’t exactly nag, but she did make hopeful noises about more grandchildren.

Eira and I weren’t certain we wanted to be parents. I was frightened that I’d pass on my mental illness; I hadn’t had a breakdown in years, but was fearful of the darkness I was sure was coded into my genes. Eira had spent her childhood caring for her younger siblings, cousins, and nieces; she was leery of surrendering her hard-won independence. She had grown up in genuine poverty -- and lived at home until she was 27, when she had moved in with me. We spent much of our disposable income on travel, clothes, jewelry, and private lessons with fitness coaches; our primary hobby, other than working out 20 hours per week, was animal rights activism. We worked very hard, and played even harder. It was a life that some mocked and others envied, and it was a life we loved – and had no small reluctance about giving up.

I’ll write soon about our time in the Los Angeles Kabbalah Centre. For years, Eira and I turned our will and our lives over to that place. Some call the Centre a cult; I would not go that far, but I can say with rueful bemusement that for the better part of a decade and a half, Eira and I did behave like cult members. We gave money we didn’t have to give ($72,000 at one point, for a new Torah scroll). We volunteered countless hours. And we took direction from our teachers about where to live, where to travel, how to decorate, how to make love.

One Saturday morning during Shabbat services, I was called to raise the Torah scroll before it was read. As soon as I had laid it back down on the bimah (the large lectern from which the Torah is read), my teacher, Yonatan, whispered in my ear. “Go right now and ask the Rav for a blessing so that you and Eira can have a child.”

The Rav was our spiritual leader. Diminished by a stroke, he sat next to the bimah through the long services, beaming and smiling at the congregation. He was said to have the power of the ruach hakodesh, the Holy Spirit; his blessings could bring prosperity, healing, and, apparently, babies.

I’m an agreeable sort; in for a penny, in for a pound and all that. I wasn’t sure the Rav had any mystical properties, but it couldn’t hurt to do as I was told. I knelt beside the aged, bearded rabbi in his cream-colored caftan; I kissed his cheek and then his hand as I had been taught.

“HaRav,” I whispered, “My wife and I would like your blessing to have a child.”

The Rav patted my hand, and whispered back. “I look forward to hearing your good news.”

The following weekend, on Friday night at midnight, in a bed and breakfast in Chico, California, Eira and I had sex without any attempt at contraception for the first time ever.

Chassidic Jews believe Friday nights at midnight are the most propitious time for baby making. It was so for us, both times.

As an aside, I am often reluctant to tell people how easy it was for Eira to get – and stay – pregnant with each of our children. So many people struggle with infertility, and so many of my friends have endured heartbreak after heartbreak, disappointment after disappointment. Eira and I conceived both Heloise and David with ease, more or less on the first try each time; the sheer stupendous luck seemed, and still seems, both unfair and undeserved. It certainly seemed too good to be true at the time – who gets pregnant on the first try?

Eira attributed our good fortune to the Rav’s somewhat enigmatic blessing. I found it hard to argue with her.

Heloise came, and then David, and when my bunny boy was 14 months old, I blew up our little world. My public self-immolation and subsequent resignation not only caused tremendous pain and embarrassment to my family, it plunged us all into financial crisis. My six-figure teaching, writing, and speaking income was gone, and in its place, a mountain of legal and medical debts. In that terrible summer and fall, Eira had to contend with a suicidal and delusional husband, two very small children, public embarrassment, and the loss of my income and benefits. She was extraordinarily resourceful, but the damage was immense.

We still live with that damage today. Our credit was ruined. With no other way to pay medical and legal bills, as well as rent, we cashed out our pensions – which bought us a little time, and huge tax debts which still hang over our heads nearly a decade later. (Eira and I owe $192,000 to the IRS and $68,000 to the California Franchise Tax Board. We don’t even have enough to make an offer-in-compromise; we simply renew our hardship referrals, year after year, forestalling the levies, while thanks to interest and penalties, the balances rise inexorably.)

I work in a grocery store and freelance on the side. Eira has a variety of gigs that help her pay the bills, but with primary custody of two children, she cannot make as much as she was able to in the past. We have no retirement savings, or emergency funds. We find ways to make it all work, but it is exhausting and scary and worlds away from what it was when we brought Heloise and David into this life.

We are still far luckier than millions of parents. We do have jobs, we can pay rent, and we can give our children the not-inconsiderable gift of two divorced people who like and respect each other. The reality, though, is between us we make only about a quarter of the money we were making 13 years ago – and our expenses are far, far greater.

As the birth rate falls across this country and around the world, many pundits point to the financial precarity of those in their prime reproductive years as a chief reason why so few are having children. This may indeed be the case; I’m not a sociologist, nor am I a demographer. What I can say is that my former wife and I chose to have children when we were as ready as any two people could have been. We had a stable marriage and stable incomes. All that good luck had seemed to defy the odds, and then the odds caught up with us, as invariably happens. All our certainties vanished with brutal and unforgiving speed, and we were forced to find a way to parent on new and terrifying terms.

Put simply, we had children in prosperity and now raise them in precarity. We are living examples of the truth that even the most seemingly blessed of couples may be living on borrowed time. I do know that my children are the greatest loves of my life, and my most important work. I do know that my humiliations and setbacks have probably made me a better, if far poorer parent. And I do know that there is no point in waiting for the perfect moment to make any sort of colossal decision, because even those perfect moments are only brief respites, like the moment a rollercoaster pauses at its apex before the certain plunge.

The song I’ve been listening to on repeat while I wrote this is from Theodora, my favorite of Handel’s operas. This aria “Racks, Gibbets, Sword and Fire” is a fun one to sing to the children, particularly when they are delaying bedtime. The soloist here is the great English bass, Callum Thorpe. He starts the aria at :59 into the video.